Understanding A, B, and C Players (as Execution Profiles)

ABC isn’t a label of worth. It’s a way to predict how someone behaves when priorities shift, ambiguity rises, and decisions get hard.

A few years ago at a UK tech unicorn, my team started using the ABC framework for one reason: we needed a clearer way to predict execution, not just assess talent.

ABC helped us see who consistently delivers outcomes — especially when the environment is messy and priorities change.

ABC helped us see who consistently delivers outcomes — especially when the environment is messy and priorities change.

This insight helps you decide what the real fix is:

- a system fix (clarify ownership, expectations, feedback loops), or

- a hiring fix (the role needs a different execution profile).

You also can listen our podcast on YouTube about this article.

TL;DR

High-performance teams aren’t built by hiring “better people.”

They’re built by matching execution needs to roles, hiring for ownership under uncertainty, and creating environments where effort turns into real impact.

A-Players aren’t defined by seniority or passion — but by how consistently they deliver outcomes when decisions are hard and responsibility is real.

They’re built by matching execution needs to roles, hiring for ownership under uncertainty, and creating environments where effort turns into real impact.

A-Players aren’t defined by seniority or passion — but by how consistently they deliver outcomes when decisions are hard and responsibility is real.

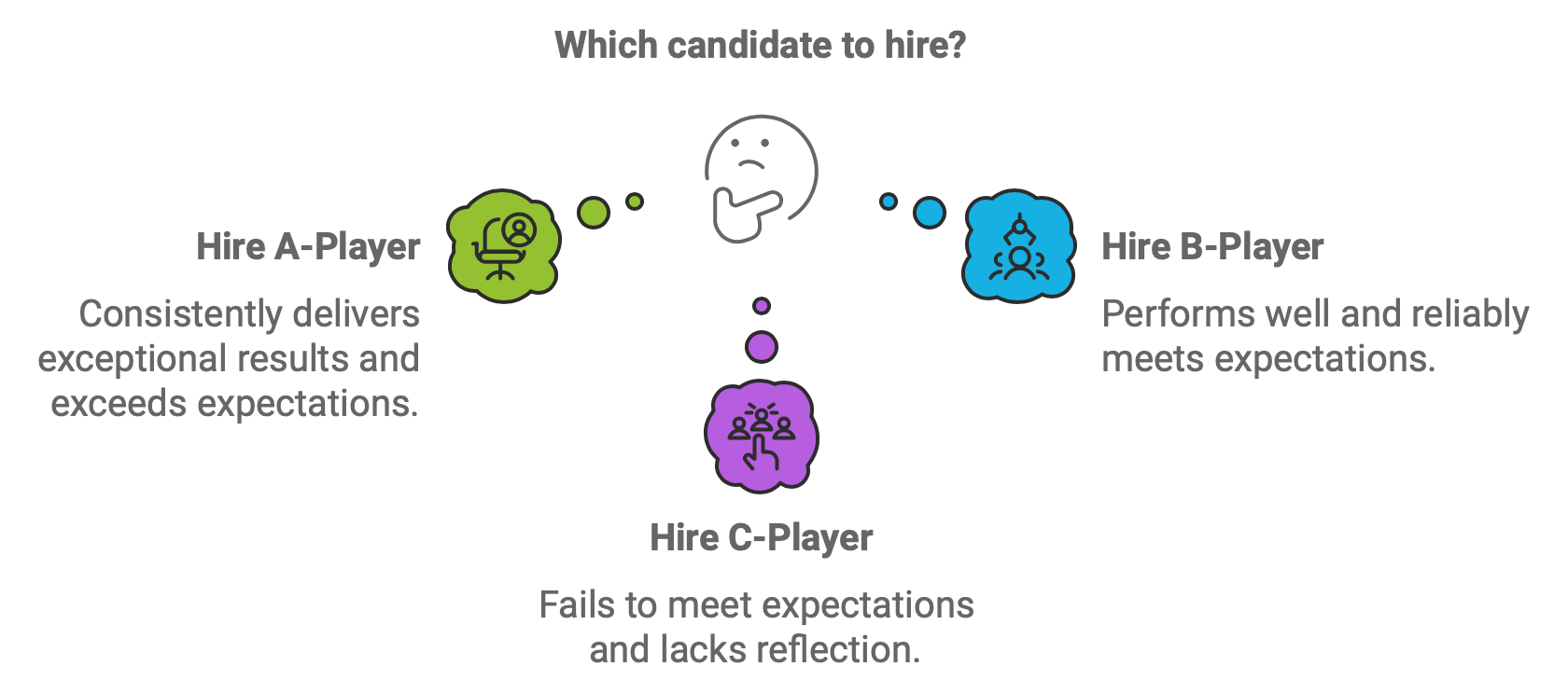

Who Are ABC Players (in Practice)?

A critical note: ABC doesn’t map to titles (junior/mid/senior) or ‘skills on paper.’

An A-Player can be junior. A senior hire can behave like a C-Player — especially when ownership is unclear and expectations are fuzzy.

ABC is about consistent output + ownership behavior.

An A-Player can be junior. A senior hire can behave like a C-Player — especially when ownership is unclear and expectations are fuzzy.

ABC is about consistent output + ownership behavior.

A-Players consistently deliver outcomes — and they create momentum.

They ask the right questions early, clarify what ‘done’ means, surface risks fast, and keep standards high without needing constant direction.

They ask the right questions early, clarify what ‘done’ means, surface risks fast, and keep standards high without needing constant direction.

B-Players execute well when the path is clear.

They’re dependable operators — but they need more structure when priorities change or ambiguity rises.

They’re dependable operators — but they need more structure when priorities change or ambiguity rises.

C-Players repeatedly miss outcomes and don’t learn fast enough.

The pattern isn’t one mistake — it’s low ownership, weak reflection, and blame shifting.

The pattern isn’t one mistake — it’s low ownership, weak reflection, and blame shifting.

The real mistake companies make isn’t hiring C-Players.

It’s hiring people without being clear which execution profile the role actually needs.

Before seniority, experience, or compensation, the first hiring decision is this:

Do we need an A-level execution profile in this role — or is a B-Player the right, sustainable choice?

It’s hiring people without being clear which execution profile the role actually needs.

Before seniority, experience, or compensation, the first hiring decision is this:

Do we need an A-level execution profile in this role — or is a B-Player the right, sustainable choice?

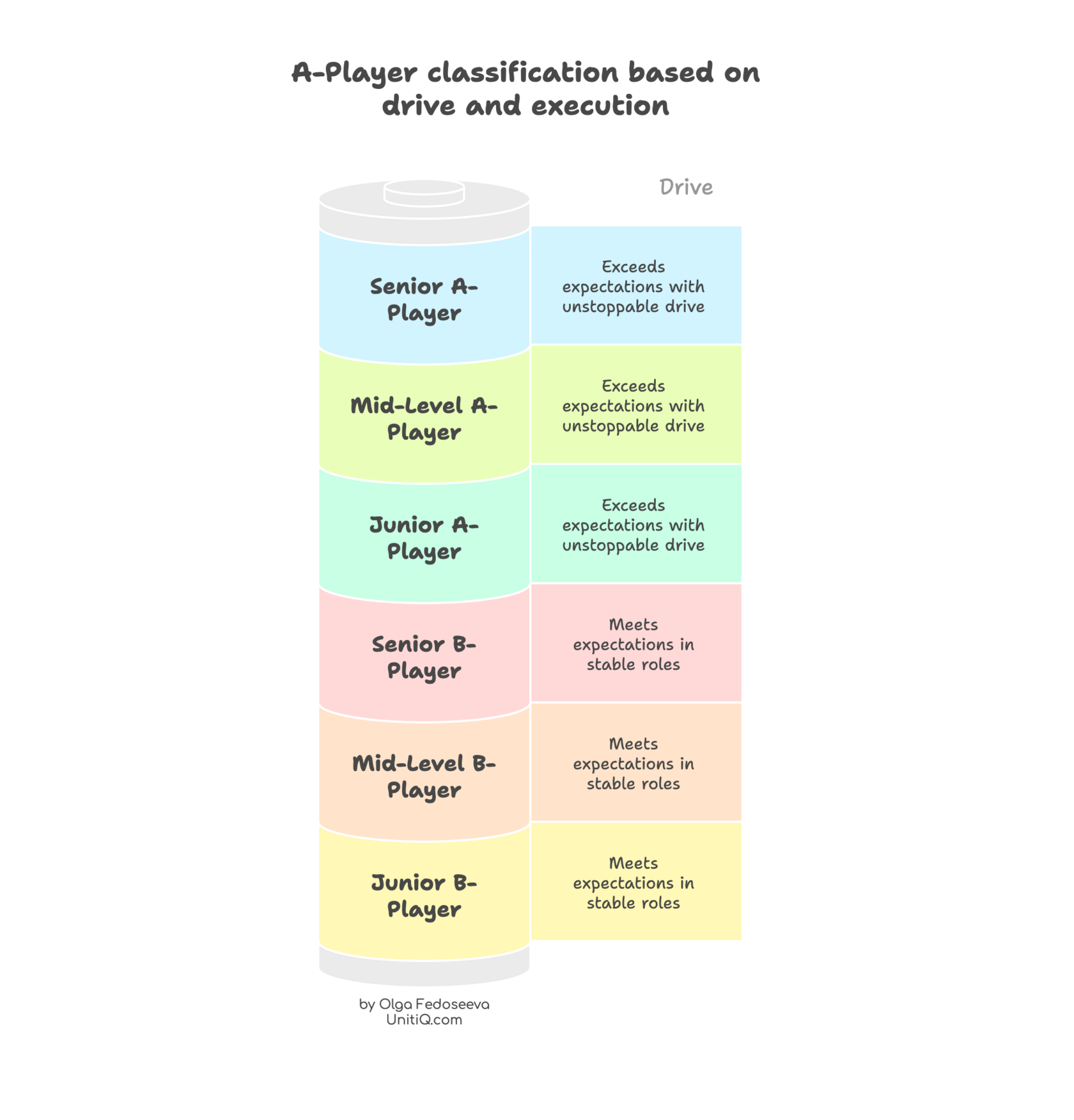

A-Player vs. Junior, Mid-Level, Senior

The ABC classification looks at a different dimension than the typical junior/mid/senior hierarchy. For example, a highly driven junior who consistently exceeds their goals in their role can be considered an A-Player.

Think of a footballer who just joined a team. They might not shine on the field yet, but their dedication in training and hunger for improvement stand out. That drive signals an A-Player, even if they haven’t yet reached a technical proficiency on par with more experienced players.

Similarly, in business, a junior employee may not have the experience of a senior but could still be an A-Player if they consistently exceed expectations and show an unstoppable drive. This approach helps evaluate the true impact of each team member.

This is why seniority alone is a weak hiring signal.

A junior A-Player can outperform a senior hire in fast-moving environments — while a senior B-Player may be perfect for stable, well-defined roles.

The mistake is not choosing “the wrong level.”

The mistake is mismatching execution expectations with the role.

A junior A-Player can outperform a senior hire in fast-moving environments — while a senior B-Player may be perfect for stable, well-defined roles.

The mistake is not choosing “the wrong level.”

The mistake is mismatching execution expectations with the role.

If you want to sanity-check what’s breaking in your hiring system, we can walk through it together.

👉 Book a conversation

👉 Book a conversation

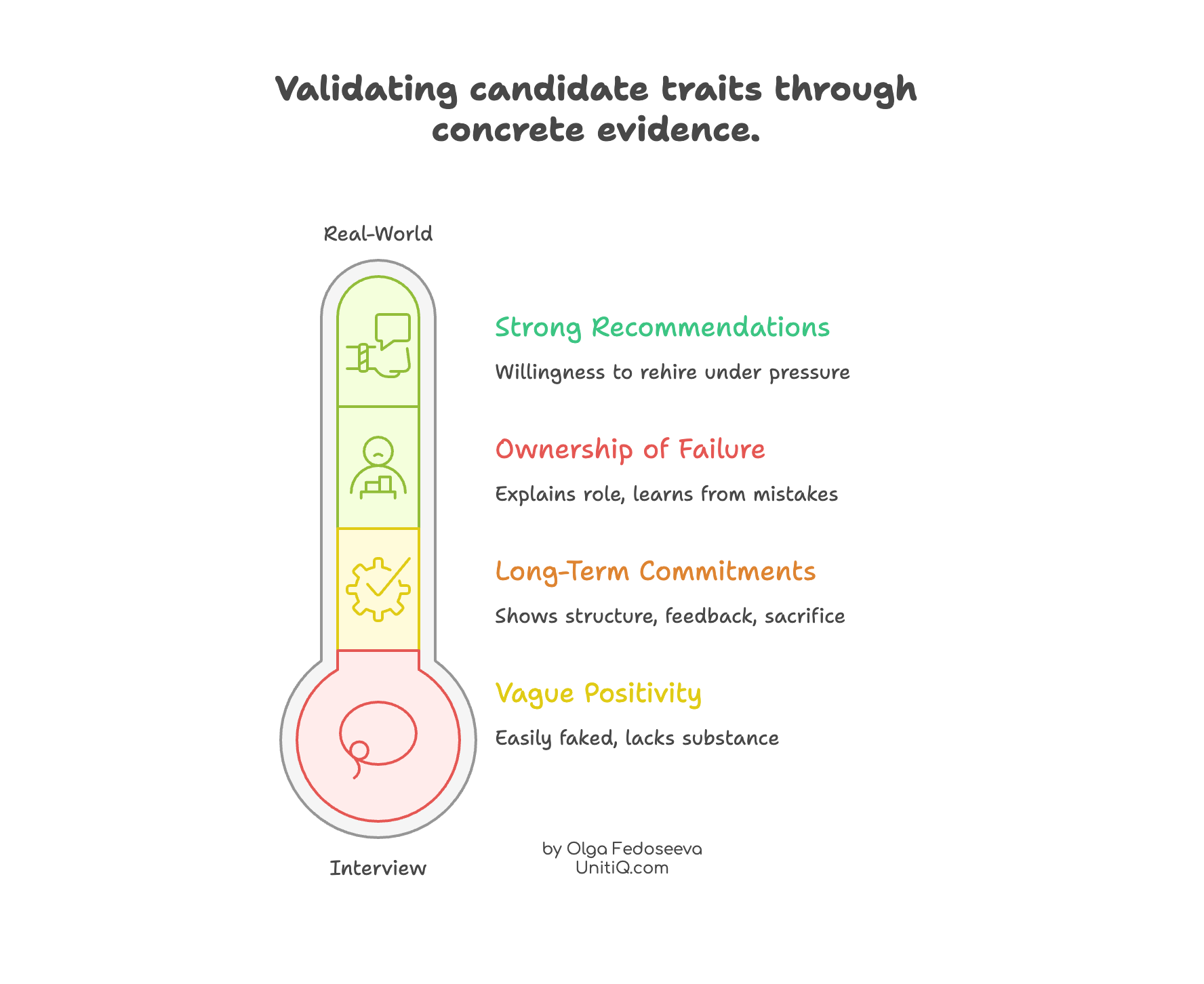

Key Traits of A-Players — and How to Test Them in Hiring

A-Players aren’t identified by enthusiasm or polished answers.

The only reliable way to spot them is by testing how they’ve behaved when ownership was real, expectations were high, and ambiguity was unavoidable.

The only reliable way to spot them is by testing how they’ve behaved when ownership was real, expectations were high, and ambiguity was unavoidable.

Strong Recommendations: The strongest indicator isn’t praise — it’s willingness.

If a former manager would rehire the candidate into a similar role under pressure, that’s a meaningful signal. Hesitation, vague positivity, or role-downgrading are red flags — even when references sound “nice".

If a former manager would rehire the candidate into a similar role under pressure, that’s a meaningful signal. Hesitation, vague positivity, or role-downgrading are red flags — even when references sound “nice".

Discipline Under Self-Direction: A-Players tend to sustain effort without external pressure.

This often shows up outside work — but not as hobbies. Look for long-term commitments that required structure, feedback, and sacrifice over time.

This often shows up outside work — but not as hobbies. Look for long-term commitments that required structure, feedback, and sacrifice over time.

Ownership of Failure: A-Players don’t just admit mistakes — they explain their role in them.

They can describe what broke, what they missed, and what they changed next time — without externalising blame.

They can describe what broke, what they missed, and what they changed next time — without externalising blame.

A quick filter:

If a signal can be faked in an interview, it’s not a signal.

If a signal can be faked in an interview, it’s not a signal.

The only traits that matter are those you can validate through:

- concrete examples

- references

- observed behavior (walk-throughs, not stories)

How People Grow Into A-Players (and Why Companies Can’t Force It)

People don’t “decide” to become A-Players.

They grow into it when three things are present:

meaningful responsibility, clear expectations, and real ownership of outcomes.

Without these conditions, even motivated people plateau — not because they lack ambition, but because the system limits their growth.

They grow into it when three things are present:

meaningful responsibility, clear expectations, and real ownership of outcomes.

Without these conditions, even motivated people plateau — not because they lack ambition, but because the system limits their growth.

Growth into an A-Player role also requires recovery and sustainability.

High ownership without recovery leads to burnout, not excellence.

High ownership without recovery leads to burnout, not excellence.

The strongest performers tend to manage their energy deliberately — whether through learning, physical routines, or structured downtime.

The signal isn’t “having hobbies.”

It’s the ability to sustain high output over time without constant external pressure.

The signal isn’t “having hobbies.”

It’s the ability to sustain high output over time without constant external pressure.

This is why “developing A-Players” can’t be a blanket strategy.

Companies can create the conditions for growth — but they can’t manufacture drive, ownership, or resilience where they don’t exist.

Companies can create the conditions for growth — but they can’t manufacture drive, ownership, or resilience where they don’t exist.

The mistake isn’t hiring B-Players.

The mistake is designing roles with A-level responsibility and B-level authority — and then wondering why execution breaks or people burn out.

The mistake is designing roles with A-level responsibility and B-level authority — and then wondering why execution breaks or people burn out.

Why Not Every Role Needs an A-Player

Not every role requires an A-level execution profile — and treating it as if it does creates unnecessary pressure and poor hiring decisions.

Some roles are stable, well-defined, and repeatable. In those environments, a strong B-Player often outperforms an A-Player by providing consistency without friction.

Problems start when companies confuse ambition with execution needs — or expect A-level ownership in roles that don’t actually have decision authority.

Problems start when companies confuse ambition with execution needs — or expect A-level ownership in roles that don’t actually have decision authority.

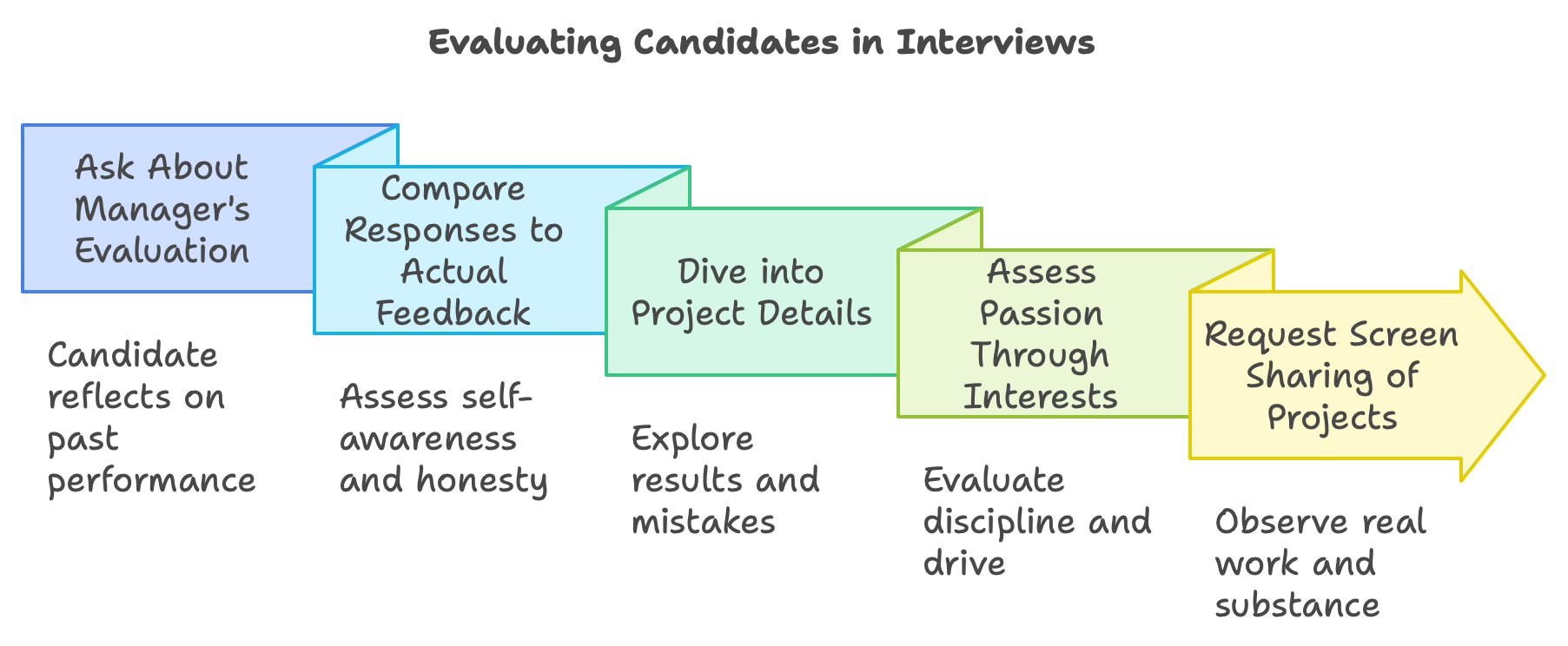

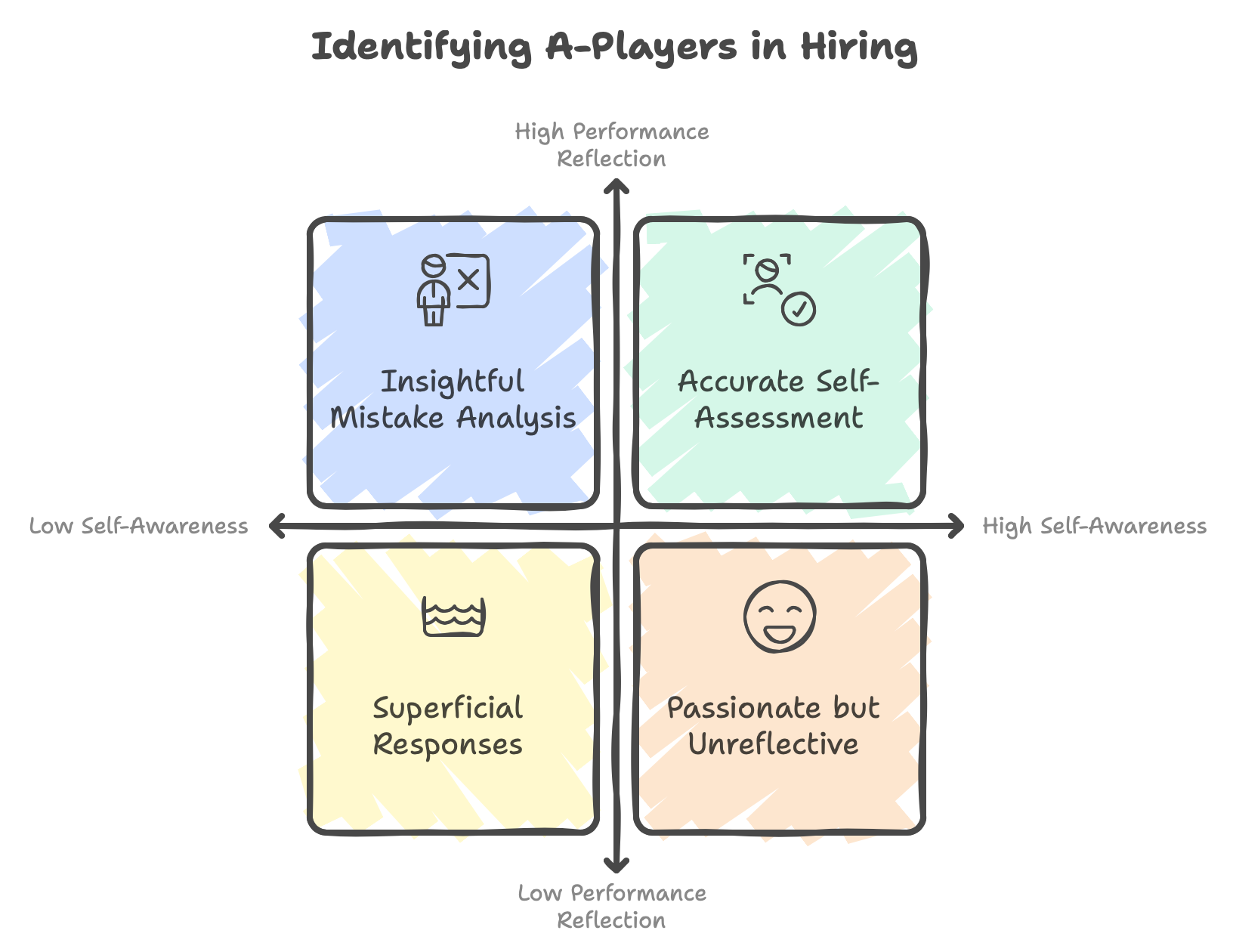

How to Spot A-Players During Hiring

The same traits that distinguish A-Players internally can be tested during hiring — but only if interviews are designed to surface real execution behavior, not polished narratives.

One powerful question during interviews is:

“When I speak with your former manager, how do you think they’ll describe your performance?”

What matters isn’t the confidence of the answer — it’s the alignment.

When a candidate’s self-assessment matches external feedback, it usually signals ownership, reflection, and consistent delivery.

“When I speak with your former manager, how do you think they’ll describe your performance?”

What matters isn’t the confidence of the answer — it’s the alignment.

When a candidate’s self-assessment matches external feedback, it usually signals ownership, reflection, and consistent delivery.

How to Evaluate Candidates During the Interview

Go deep into specifics. Ask about outcomes, trade-offs, and moments where execution broke down.

The signal isn’t the mistake itself — it’s whether the candidate can clearly explain:

A-Players show clarity and accountability. Weak candidates stay abstract or externalize blame.

The signal isn’t the mistake itself — it’s whether the candidate can clearly explain:

- what they owned

- where they misjudged the situation

- what they changed the next time

A-Players show clarity and accountability. Weak candidates stay abstract or externalize blame.

Dive into specifics—ask about results, how they were achieved, and what mistakes were made. It’s not the errors themselves that matter but how deeply the candidate reflects on them and the lessons they’ve drawn from those experiences.

You also want to explore their interests. The depth of their passion—whether it’s for sports, literature, or any other field—can signal discipline and a drive for self-actualization. For instance, someone running weekly might not show much, but someone who trains for marathons likely has the dedication you’re looking for.

One of the most reliable ways to test execution is to ask candidates to share their screen and walk through a real project they’ve owned.

Stories can be rehearsed. Screens can’t.

Pay attention to how they explain decisions, constraints, and trade-offs — not just outcomes. This is where true ownership (or lack of it) becomes obvious.

Stories can be rehearsed. Screens can’t.

Pay attention to how they explain decisions, constraints, and trade-offs — not just outcomes. This is where true ownership (or lack of it) becomes obvious.

A simple rule helps avoid most hiring mistakes:

If a signal can be faked in a 60-minute interview, it’s not a signal.

Prioritise evidence that requires consistency over time — not confidence in the moment.

If a signal can be faked in a 60-minute interview, it’s not a signal.

Prioritise evidence that requires consistency over time — not confidence in the moment.

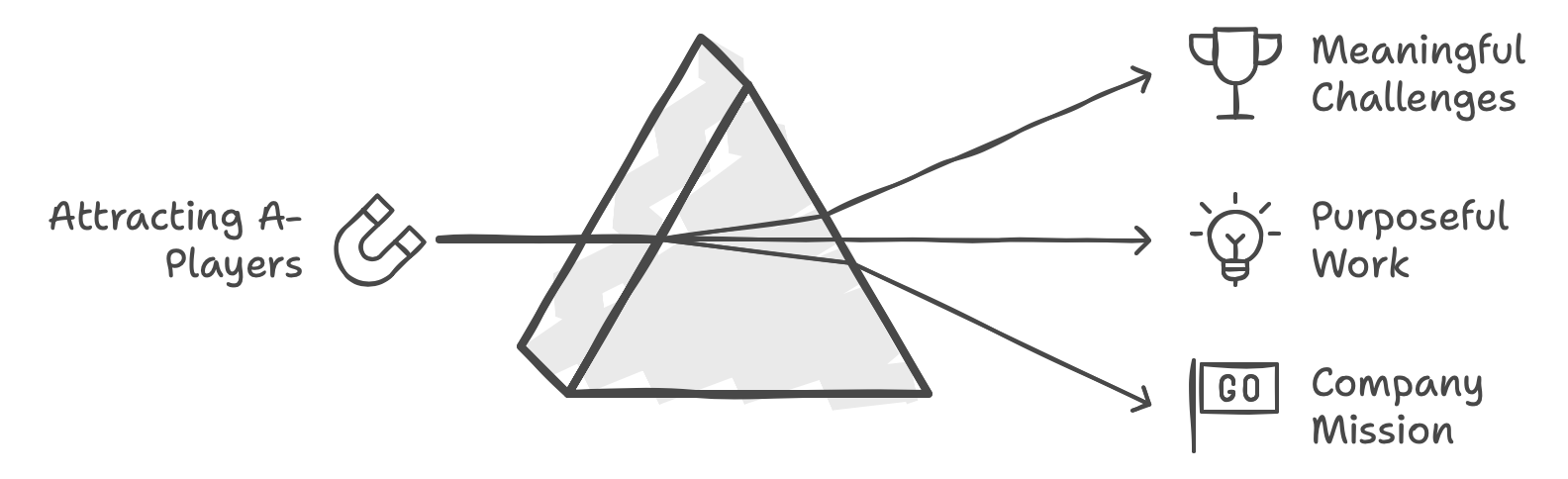

What Actually Attracts A-Players (and What Quietly Repels Them)

Not every company is designed to attract A-Players — and that’s fine.

A-Players are selective because they’re optimizing for impact, not comfort.

They look for roles where effort translates directly into outcomes, and where responsibility is real — not symbolic.

Compensation needs to be fair, but beyond a threshold it stops being the deciding factor. What matters more is whether their work will actually move something meaningful forward.

A-Players are selective because they’re optimizing for impact, not comfort.

They look for roles where effort translates directly into outcomes, and where responsibility is real — not symbolic.

Compensation needs to be fair, but beyond a threshold it stops being the deciding factor. What matters more is whether their work will actually move something meaningful forward.

Purpose matters to A-Players — but not as a slogan.

They look for environments where the mission shows up in everyday decisions:

When purpose is reflected in execution, A-Players commit deeply. When it’s disconnected, they disengage fast.

They look for environments where the mission shows up in everyday decisions:

- what gets prioritised

- what gets funded

- what gets cut

When purpose is reflected in execution, A-Players commit deeply. When it’s disconnected, they disengage fast.

A company’s mission acts as a filter, whether leaders intend it or not.

When the mission has real constraints and trade-offs, it attracts people who want responsibility and impact.

When it’s vague or decorative, it attracts candidates who are motivated by security, status, or convenience instead.

When the mission has real constraints and trade-offs, it attracts people who want responsibility and impact.

When it’s vague or decorative, it attracts candidates who are motivated by security, status, or convenience instead.

A-Players don’t join companies because they feel inspired on day one.

They join because they see a place where decisions matter, ownership is real, and effort won’t be wasted.

They join because they see a place where decisions matter, ownership is real, and effort won’t be wasted.

Final Thoughts

Building a team of A-Players is a powerful strategy for driving a company’s success. Talent acquisition should focus not just on filling roles but on finding individuals whose ambition and dedication align with your company’s vision. Fractional HR services like those offered by UnitiQ can be a game-changer in this regard, especially for smaller businesses that need top-tier people management without the cost of a full-time HR team. By strategically using fractional HR, companies can enhance their hiring process and ensure they are attracting and retaining A-Players who can lead them to long-term growth.

In conclusion, focusing on hiring and nurturing A-Players is a long-term investment that leads to significant returns, both in team performance and company culture. However, it’s essential to strike a balance and recognize that B-Players also have valuable roles, ensuring the team functions cohesively.

I also recommend you to read related articles:

How Growing and Scaling Businesses Can Attract Top Talent: Proven HR Strategies for Success

HR Branding: The Key to Attracting Talent and Building Long-Term Loyalty

5 Hiring Hacks Every Founder Needs to Attract Top Talent Fast

UnitiQ’s Method for Sourcing and Developing Top Engineering Talent

We help to building teams with right skills and based on your value

I also recommend you to read related articles:

How Growing and Scaling Businesses Can Attract Top Talent: Proven HR Strategies for Success

HR Branding: The Key to Attracting Talent and Building Long-Term Loyalty

5 Hiring Hacks Every Founder Needs to Attract Top Talent Fast

UnitiQ’s Method for Sourcing and Developing Top Engineering Talent

We help to building teams with right skills and based on your value

Listen on Youtube

Author

Olga Fedoseeva is an award-winning HR executive and people strategist with over 20 years of international experience across EMEA, the US, and APAC. Currently Chief of Staff at Exponential Science and Founder of UnitiQ, she has personally hired more than 1,000 employees and scaled organizations from 30 to 3,000 staff. Recognized as one of the Top HR Women in EV (2021), Olga has led global HR transformation, talent acquisition, and people operations for startups, scale-ups, and multinational enterprises. Her expertise spans the full HR lifecycle—succession planning, DEI, HR tech integration, workforce planning, and executive coaching—helping businesses align people strategies with growth objectives while fostering inclusive, high-performance cultures.