Most founders don’t say “our hiring process is broken.”

They say things like:

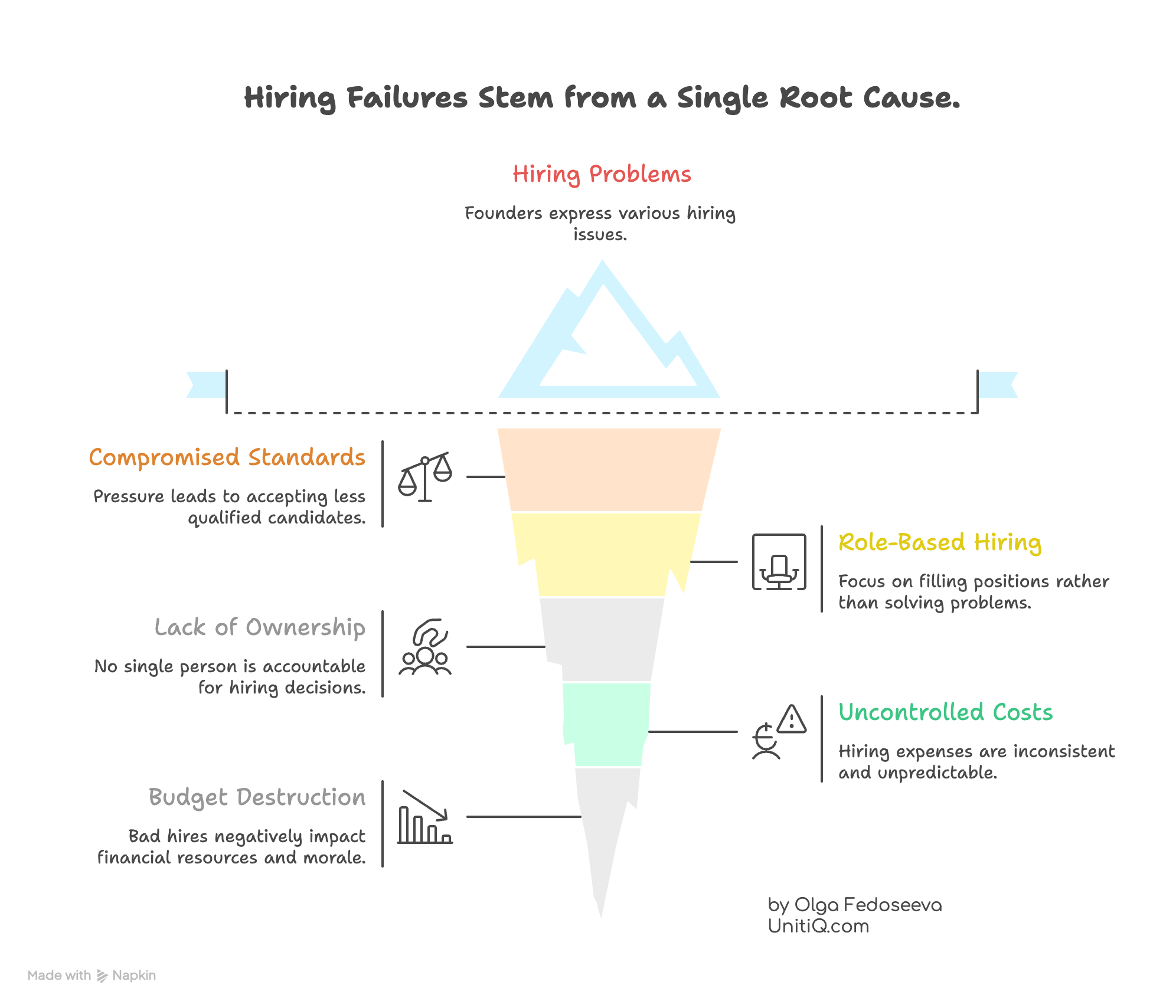

- “I spend too much time reviewing candidates who are almost right but not good enough.”

- “We keep compromising because we’re under pressure to fill roles.”

- “We’re hiring roles, not actually solving problems.”

- “Everyone has an opinion, but no one owns the decision.”

- “Hiring costs are all over the place.”

- “Bad hires quietly destroy our budget and morale.”

These sound like separate problems.

They’re not.

They’re all the same failure showing up in different places.

The pattern founders miss

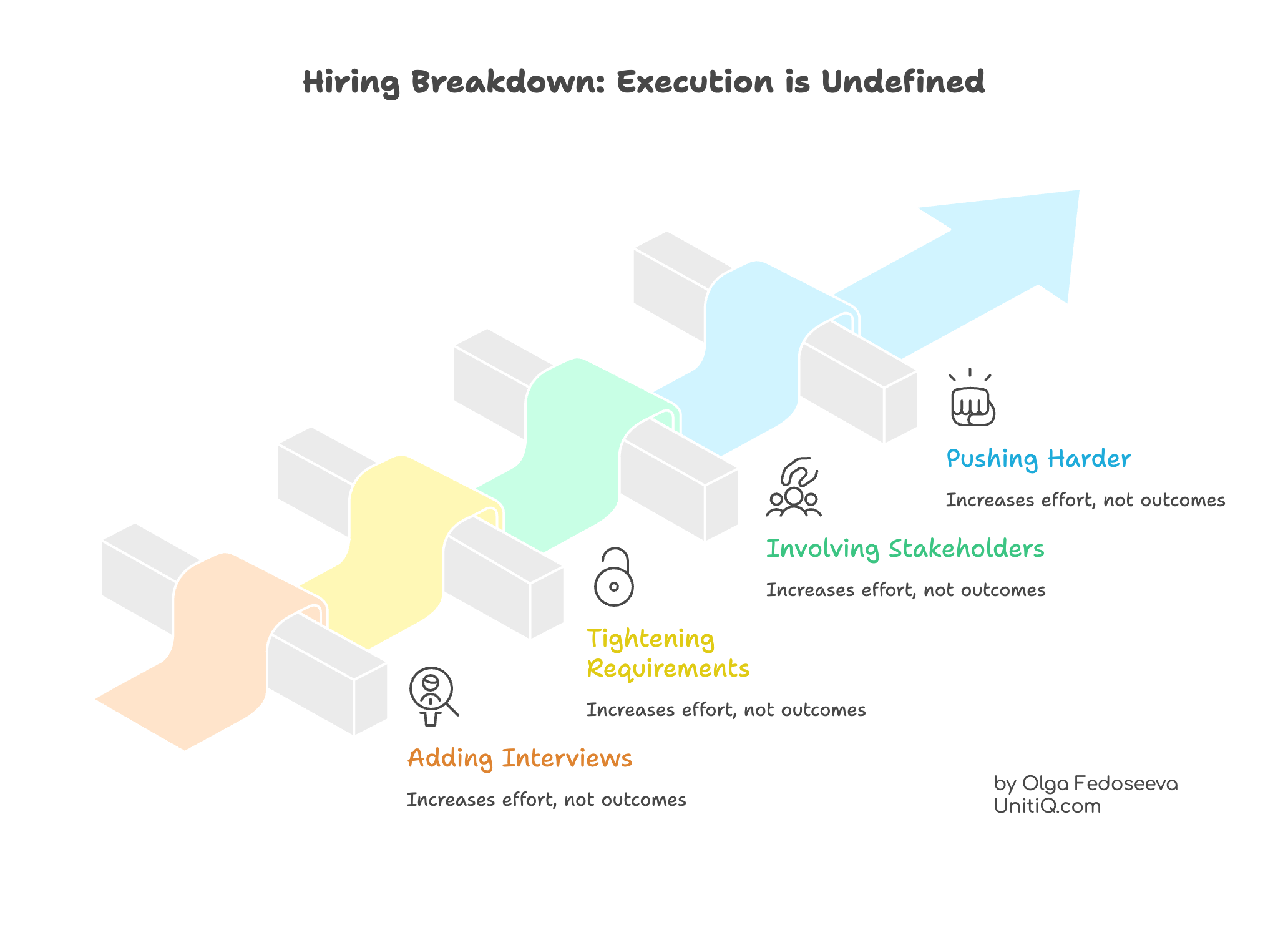

When hiring breaks at Series A–C, founders usually respond by:

- adding interviews

- tightening requirements

- involving more stakeholders

- pushing harder to “get it done”

This increases effort — but rarely improves outcomes.

Why?

Because the issue isn’t candidate quality.

It’s not recruiter performance.

It’s not even speed.

The issue is that execution is undefined.

And when execution is unclear, hiring can’t work — no matter how hard you push.

Hiring feels broken because hiring isn’t the bottleneck — execution capacity is.

Why “almost right” candidates keep showing up

Founders often say:

“The candidates are good… just not quite right.”

This isn’t bad luck.

It’s what happens when:

- roles are defined as skill lists

- success is described vaguely (“senior”, “strong”, “independent”)

- execution expectations live in founders’ heads

Candidates are evaluated against proxies, not outcomes.

So you get:

- impressive CVs

- confident interviews

- and weak execution once hired

Hiring feels subjective because it is.

This happens when roles are defined by skills and seniority instead of execution ownership. We break down this failure — and how to fix it — in How Startups Define Roles Wrong (And Why They Keep Hiring “Almost Right” People).

Why teams start compromising under pressure

When execution isn’t clearly defined:

- there’s no hard “yes” or “no”

- urgency overrides quality

- teams lower the bar without naming it

This creates a dangerous loop:

- Pressure to hire increases

- Standards become flexible

- Mis-hires increase

- Execution slows

- Pressure increases further

Founders experience this as:

“We had no choice — we needed someone.”

In reality, the system gave them no safe alternative.

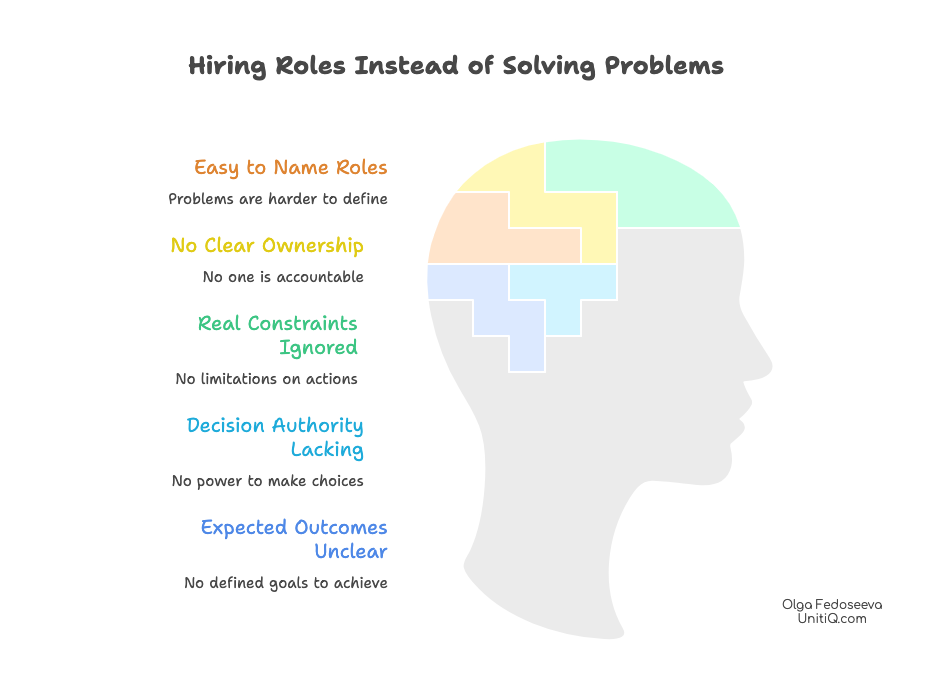

Why you’re hiring roles instead of solving problems

Roles are easy to name.

Problems are harder to define.

So startups default to:

- “We need a Senior X”

- “We need someone experienced”

- “We need to add capacity”

But roles don’t execute.

People solving specific problems do.

When hiring isn’t anchored to:

- clear ownership

- real constraints

- decision authority

- expected outcomes

…you hire capacity instead of capability.

And capacity without direction adds noise, not leverage.

The impact of unclear roles isn’t uniform — execution breaks differently across teams.

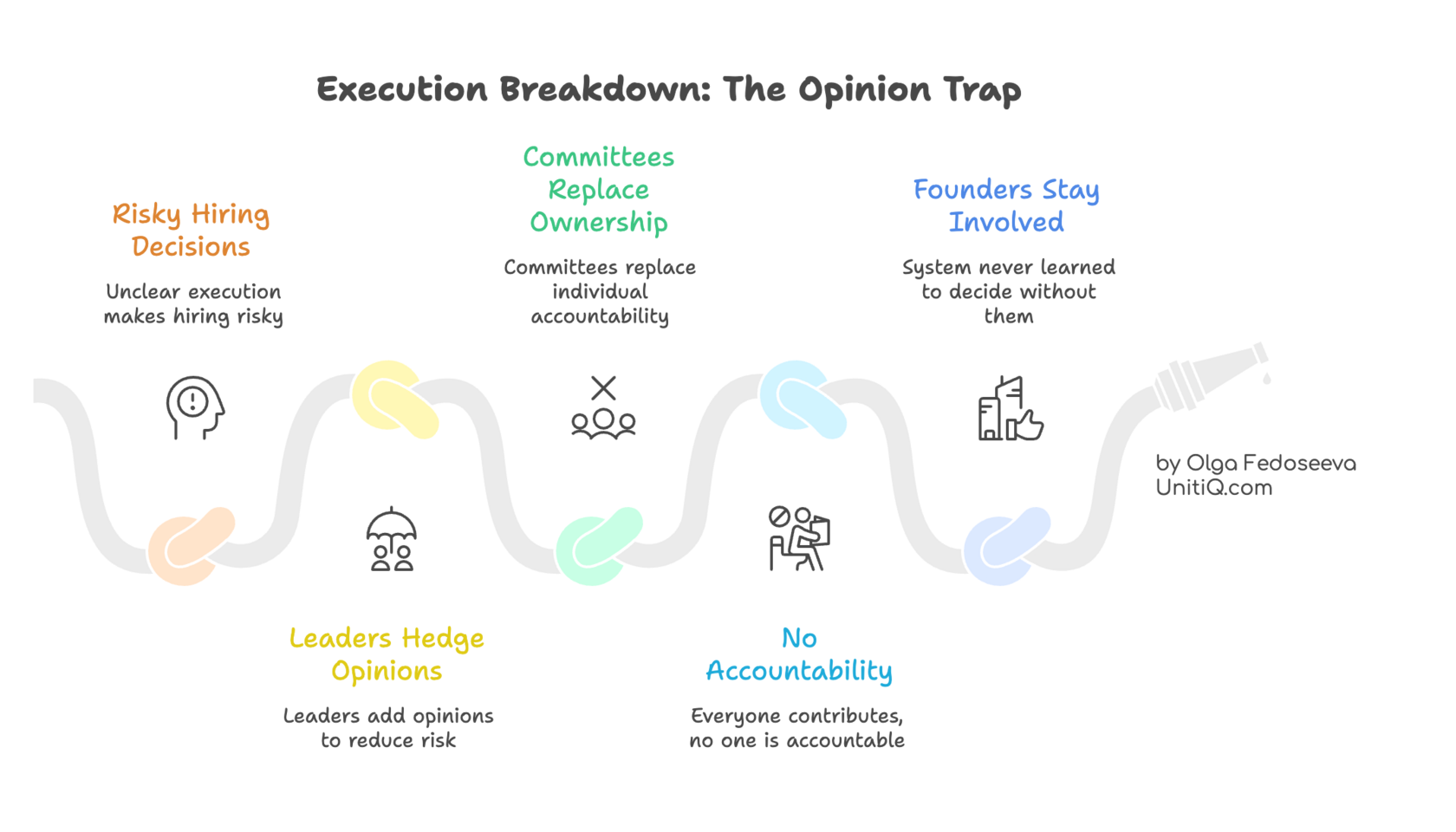

Why everyone has an opinion — and no one owns the decision

This is one of the clearest signals of execution breakdown.

When execution is unclear:

- hiring decisions feel risky

- leaders hedge by adding opinions

- committees replace ownership

Everyone contributes input.

No one carries accountability.

Founders stay involved not because they want to —

but because the system never learned to decide without them.

Hiring slows. Confidence drops. Momentum leaks.

When decision ownership is unclear, opinions replace accountability and founders stay involved. We explain why this happens — and how to restore ownership — in Why Everyone Has an Opinion but No One Owns Hiring Decisions.

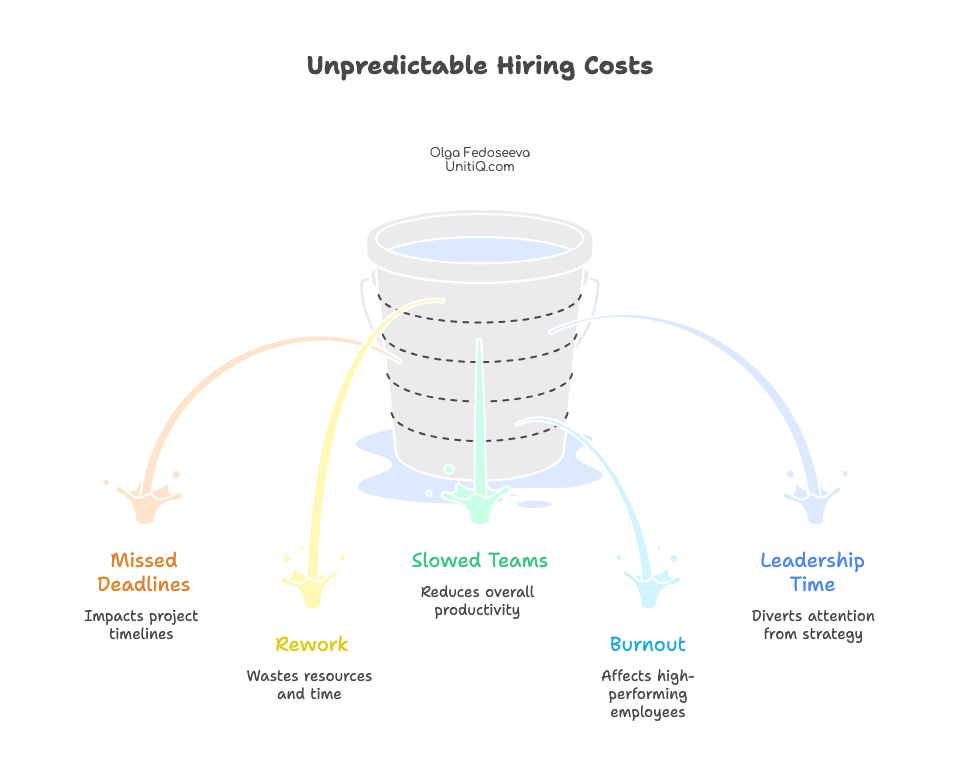

Why hiring costs feel unpredictable

Founders often track:

- agency fees

- recruiter spend

- salaries

But the real cost of hiring failure shows up elsewhere:

- missed deadlines

- rework

- slowed teams

- burnout in high performers

- leadership time

These costs don’t sit under “hiring.”

They show up months later, across the org.

That’s why hiring feels expensive without looking expensive on paper.

Why bad hires quietly destroy morale

Bad hires rarely fail loudly.

Instead, they:

- create friction

- shift work onto others

- slow decisions

- lower trust

- drain energy

High performers compensate — until they burn out.

Teams stop believing change will stick.

Execution becomes fragile.

Founders often notice this after morale drops — not when the hire was made.

The real damage of a bad hire rarely shows up as hiring cost — it shows up later as slowed execution, burnout, and founder overload. We unpack where this cost actually appears in The Real Cost of a Bad Hire (Why It Never Shows Up Where You Expect).

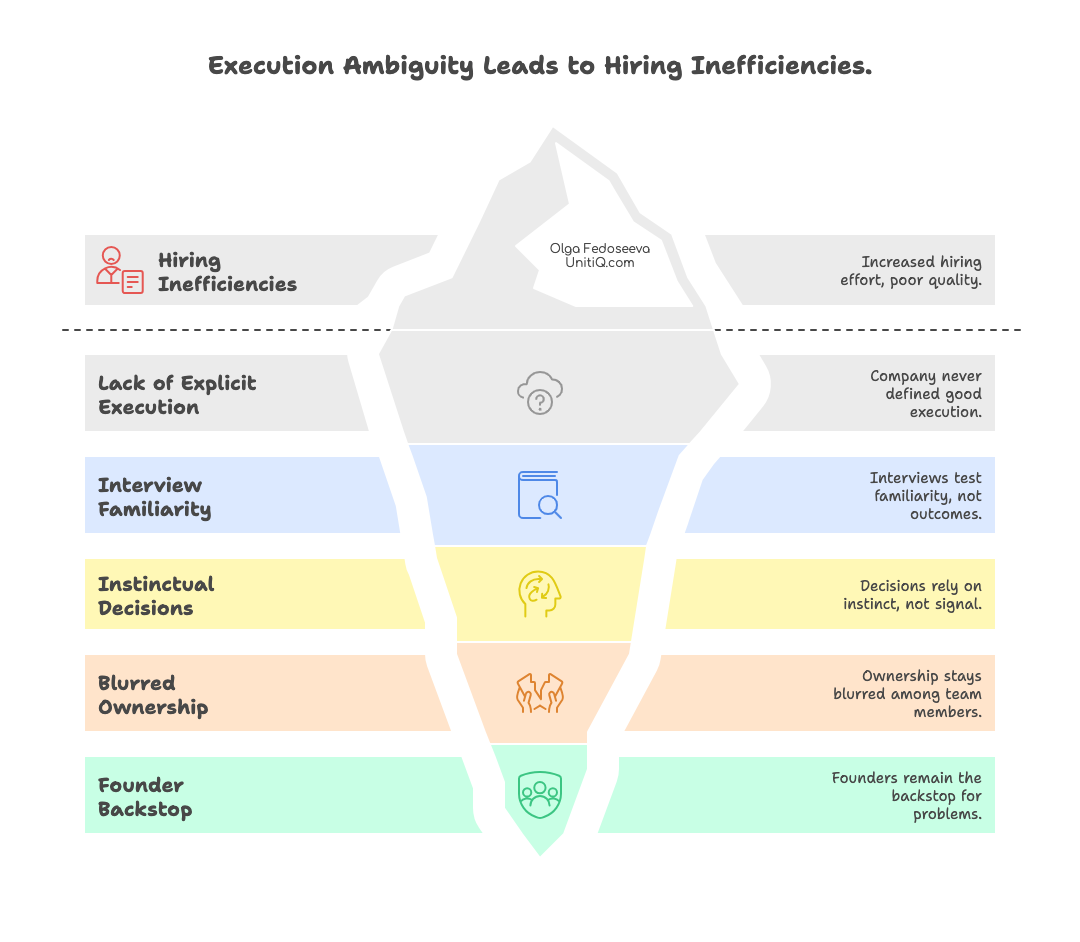

The root cause: execution was never made explicit

These problems are not independent.

They are symptoms of one underlying issue:

The company never defined what good execution looks like — per role, per stage.

Without that:

- interviews test familiarity, not outcomes

- decisions rely on instinct, not signal

- ownership stays blurred

- founders remain the backstop

Hiring effort increases.

Hiring quality does not.

Why hiring effort won’t fix this

More interviews won’t:

- clarify ownership

- define execution

- reduce compromise

- protect morale

Better sourcing won’t:

- fix role ambiguity

- resolve decision paralysis

- stop founder involvement

This is not a hiring volume problem.

It’s a system design problem.

What actually changes hiring outcomes

At Series A–C, hiring starts working when companies:

- define execution outcomes before opening roles

- design interviews to test real work, not narratives

- assign clear decision ownership

- align onboarding to execution expectations

- treat hiring as part of a broader People Project

This is how founders get out of hiring mode — not by delegating harder, but by building clarity into the system.

Key Takeaways (TL;DR)

- If startup hiring feels slow, subjective, or exhausting, the problem is rarely candidate quality — it’s undefined execution.

- “Almost right” candidates appear when roles are defined by skills and seniority instead of outcomes and ownership.

- Compromising under pressure is a system failure, not a discipline problem.

- When everyone has an opinion in hiring, it usually means no one owns the decision.

- Hiring costs feel unpredictable because the real damage of mis-hires shows up later — in missed deadlines, burnout, and lost momentum.

- Bad hires rarely fail loudly; they quietly erode morale, trust, and execution speed.

- More interviews, more stakeholders, or more hiring effort won’t fix this.

- Hiring improves when execution expectations are made explicit, decision ownership is clear, and hiring is treated as part of a broader People Project.

What comes next

If this article resonated, the next questions are logical:

- How exactly are roles misdefined — and how do you fix that?

- Why decision ownership breaks during scale?

- Where do bad hires actually do the most damage?

Each of those deserves its own deep dive.

This article is the diagnosis.

The next ones are about the fix.

The problems described here don’t exist in isolation. They compound as startups scale — starting with vague role definitions, breaking further with unclear decision ownership, and ending with invisible execution damage from mis-hires. Each of these deserves its own deep dive.

If this sounds familiar, you’re not dealing with a hiring problem — you’re dealing with an execution problem.

UnitiQ works with Series A–C tech founders to redesign hiring around execution, ownership, and real outcomes — so hiring stops slowing the company down.

If you want to sanity-check what’s breaking in your hiring system, we can walk through it together.

👉 Book a conversation

UnitiQ works with Series A–C tech founders to redesign hiring around execution, ownership, and real outcomes — so hiring stops slowing the company down.

If you want to sanity-check what’s breaking in your hiring system, we can walk through it together.

👉 Book a conversation

About the author

Olga Fedoseeva is the Founder of UnitiQ, a talent acquisition and People Projects partner for Series A–C tech startups across EU, UKI, and MENA.

She works with founders in Fintech, AI, Crypto, and Robotics who are stuck in hiring or execution mode — helping them restore momentum by redesigning hiring around execution, ownership, and real outcomes.