Founders often describe the same hiring frustration in different words:

“They’re good… but not quite.”

“Strong CV, something feels off.”

“We liked them, but couldn’t fully commit.”

This isn’t bad intuition.

It’s a system problem.

When execution is undefined, every candidate becomes “almost right.”

This happens because hiring is not the bottleneck — execution capacity is.

“Almost Right” Is What Hiring Sounds Like When No One Can Define Success

Founders often interpret “almost right” as a judgment about the candidate.

It isn’t.

It’s the symptom of a hiring system that never defined success in execution terms.

When no one can articulate what must be true after this person joins —

what decisions they must own, what problems must move, what ambiguity they must absorb — every candidate feels close, but never convincing.

Early on, founders compensate for this with intuition and proximity.

As the company scales, that compensation disappears.

“Almost right” doesn’t mean standards are high.

It means the target was never clear.

The Real Problem Isn’t Talent — It’s Undefined Execution

Most hiring processes start with a role description.

Very few start with an execution definition.

That gap is exactly what must be true before you hire — and most teams skip it.

That gap creates uncertainty.

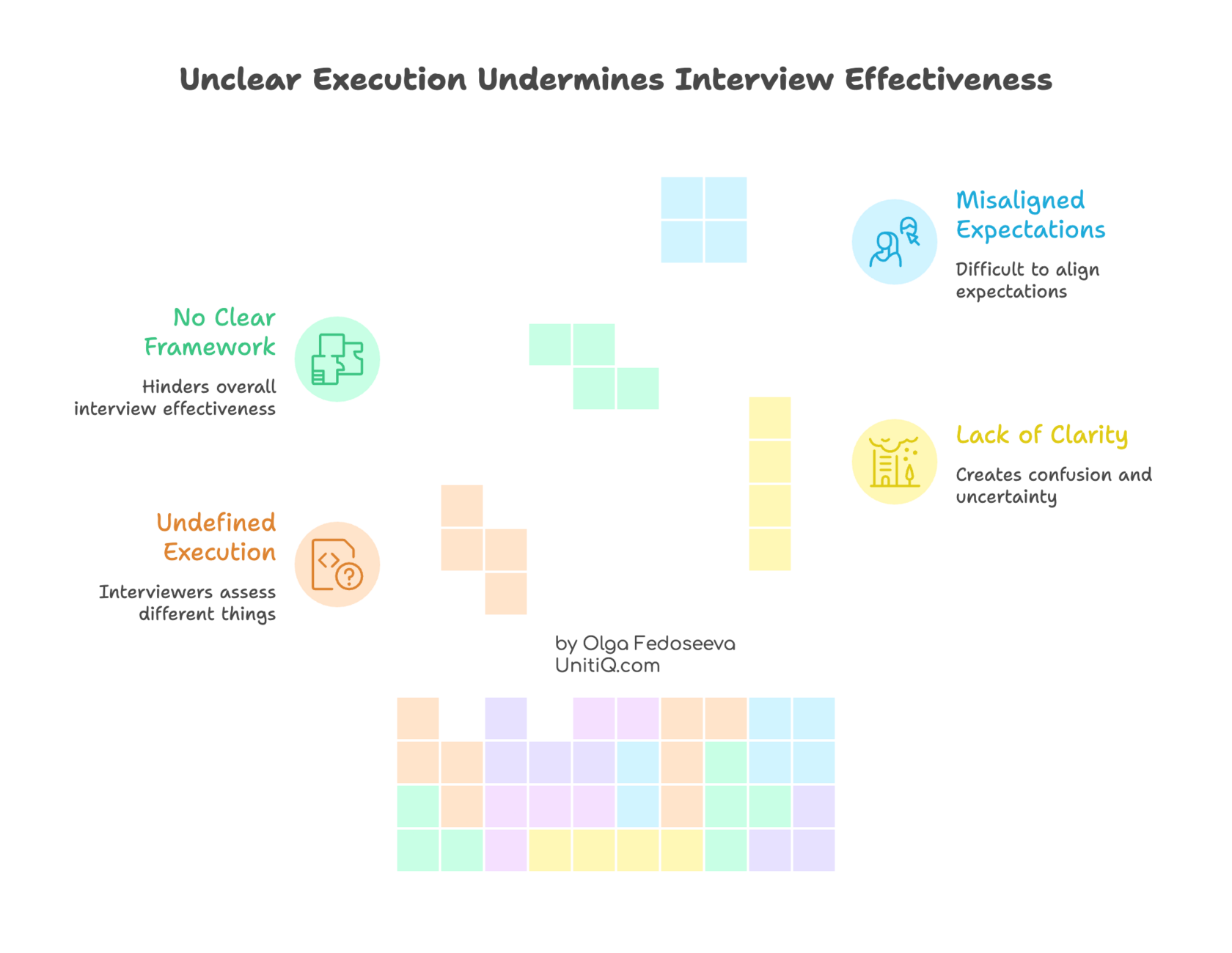

When execution isn’t explicitly defined:

- Interviewers assess different things

- Signals conflict instead of reinforce

- Confidence erodes instead of compounds

The result isn’t a bad hire — it’s no hire, slow hire, or compromised hire.

This pattern sits inside a larger problem: uncertainty in talent acquisition drains leadership attention far more than difficult work ever does.

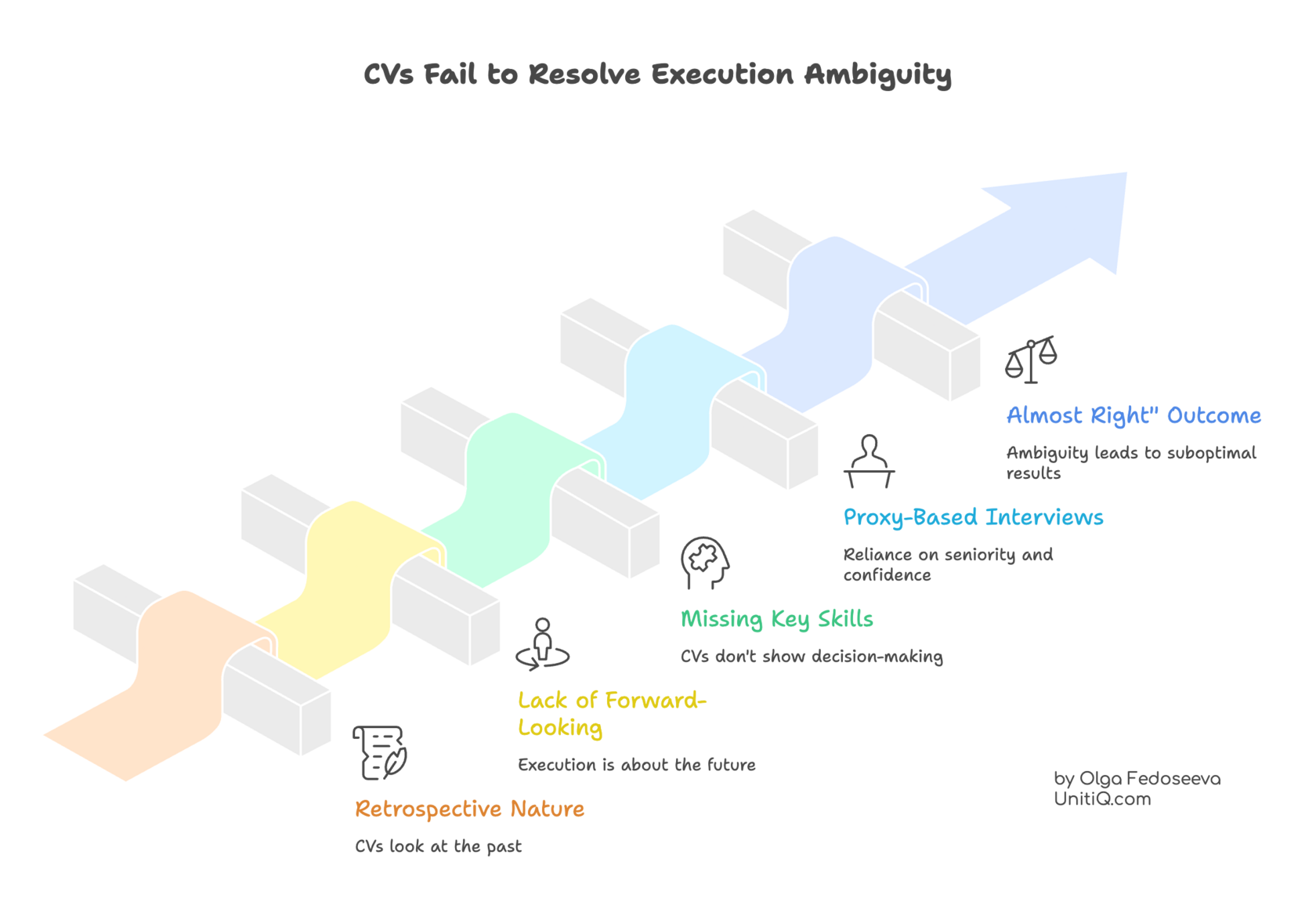

Why CVs Can’t Resolve Execution Ambiguity

CVs are retrospective.

Execution is forward-looking.

A CV tells you:

- Where someone worked

- What titles they held

- What they’ve been exposed to

It does not tell you:

- How they decide under uncertainty

- How they prioritize when trade-offs collide

- How they act when context changes mid-stream

When execution expectations aren’t defined, interviews default to proxies:

- Seniority

- Confidence

- Familiar brands

- “Gut feel”

That’s how “almost right” becomes the dominant outcome.

Even when execution is partially understood, hiring rarely moves forward if no one clearly owns the hiring decision. Signals stack up, opinions multiply, and “almost right” keeps repeating instead of resolving.

This is the exact moment when talent acquisition breaks because no one owns the decision.

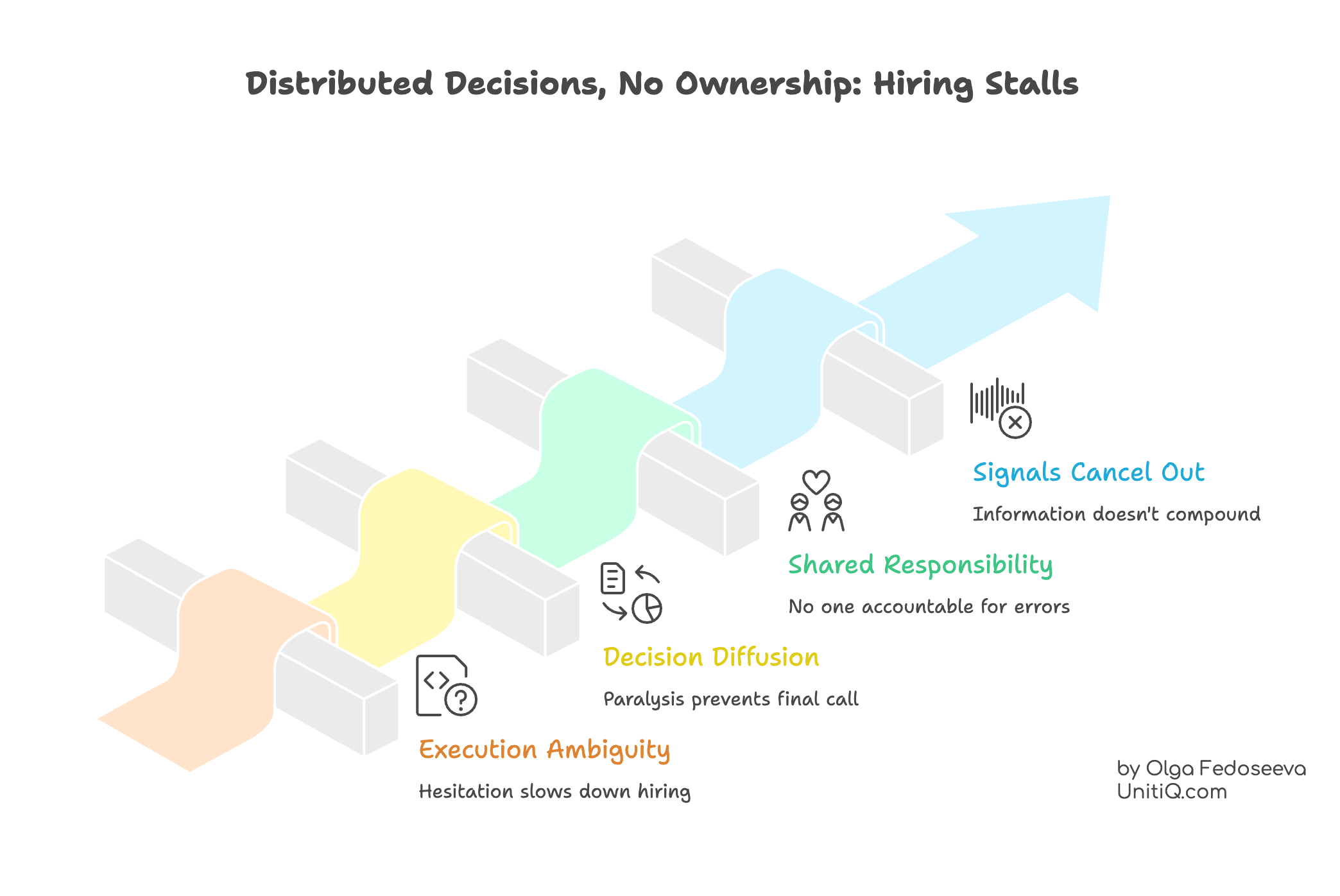

“Almost Right” Persists When Decisions Are Distributed but Ownership Isn’t

Execution ambiguity explains hesitation.

Decision diffusion explains paralysis.

When multiple interviewers assess different risks, when responsibility for the final call is shared, and when no one is clearly accountable for being wrong, “almost right” becomes the safest outcome.

Not because the candidate is weak —

but because commitment feels riskier than delay.

Signals don’t compound.

They cancel each other out.

Hiring stalls not from lack of information, but from lack of ownership.

Execution Definition Changes the Interview Question Entirely

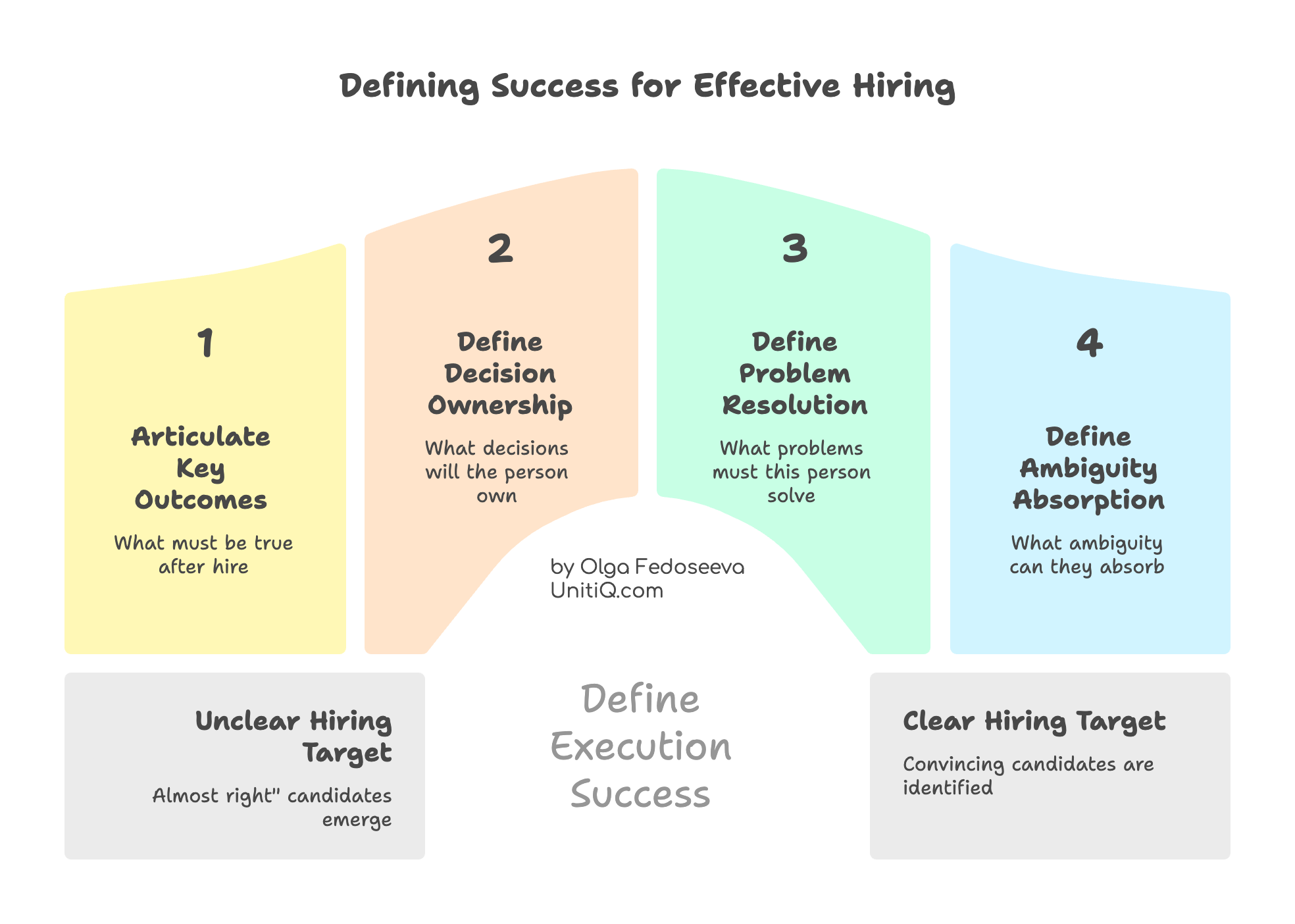

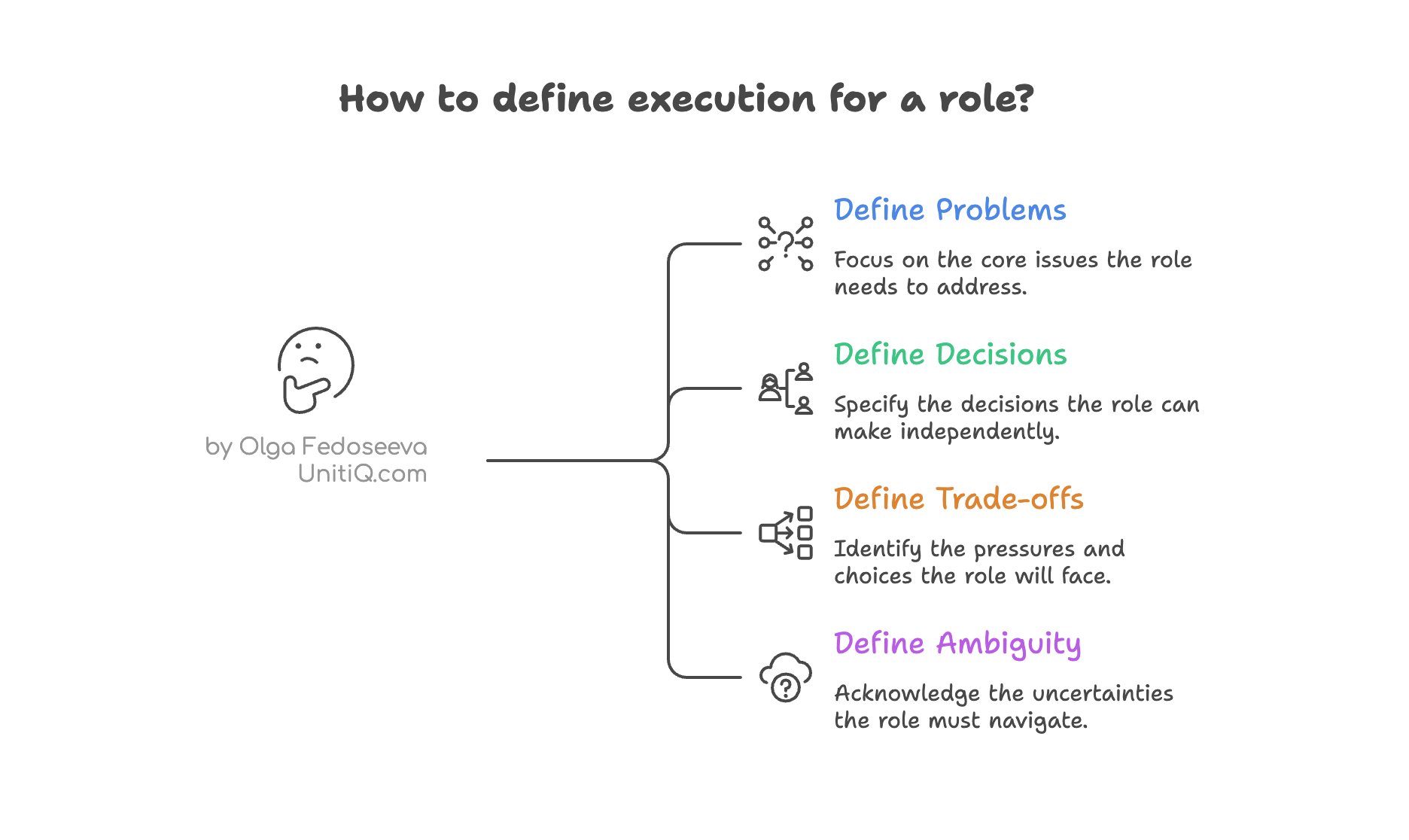

Execution-focused hiring starts by answering one question before sourcing candidates:

What must be true in 90 days for this hire to be considered successful?

A real execution definition includes:

- Problems the role must own (not tasks)

- Decisions the role must make without escalation

- Trade-offs the role will face under pressure

- Ambiguity the role must operate within

Once this is clear:

- Interview questions converge

- Signals align

- Confidence increases

- Decisions become faster — and owned

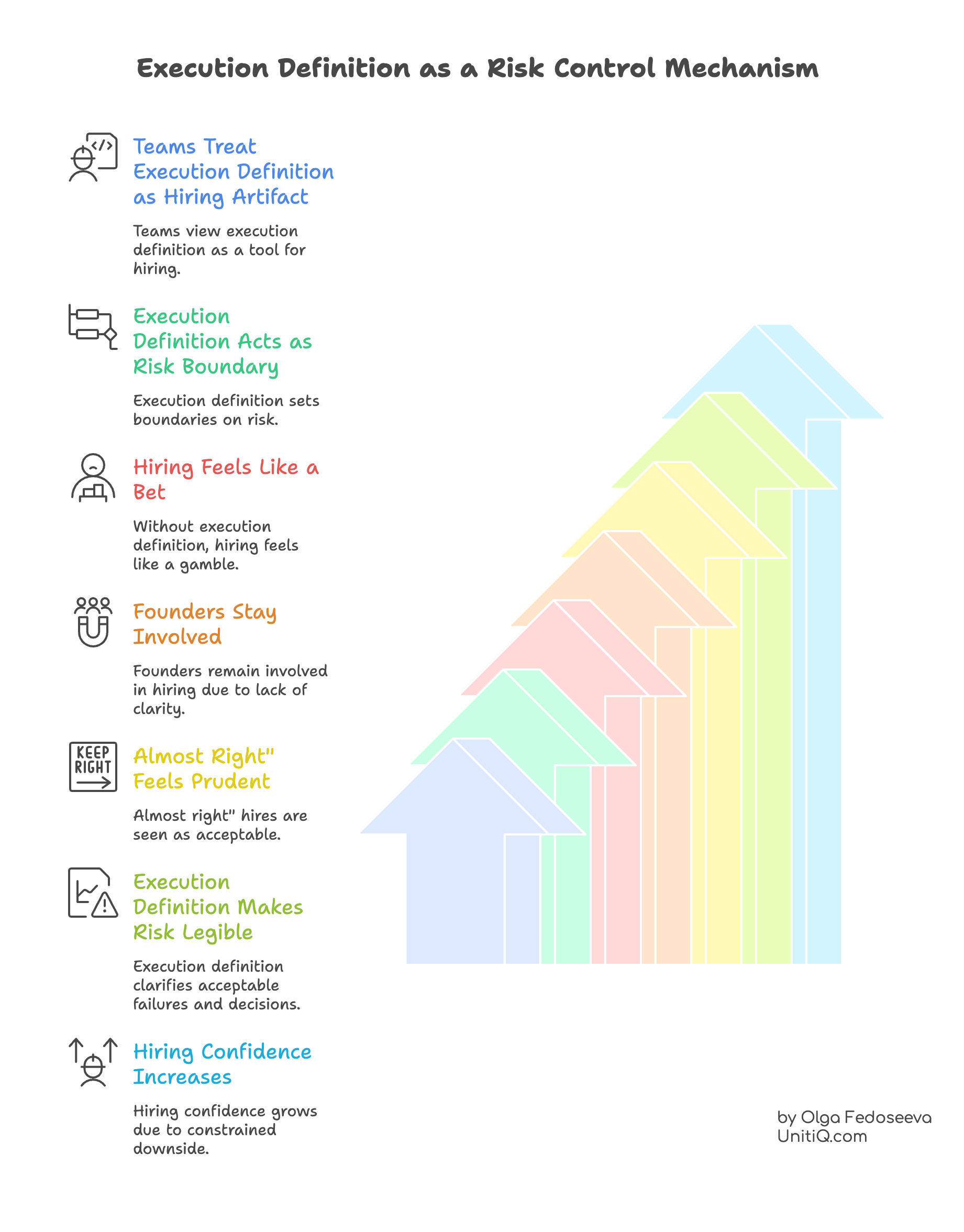

Execution Definition Is Not a Hiring Tool — It’s a Risk Control Mechanism

Most teams treat execution definition as a hiring artifact.

In reality, it’s a boundary on risk.

Without it, every hire feels like a bet, founders stay involved by necessity, and “almost right” feels prudent instead of costly.

Execution definition makes risk legible.

It clarifies which failures are acceptable, which decisions the role must absorb without escalation, and where ambiguity is unavoidable.

Hiring confidence increases not because candidates improve —

but because downside becomes constrained.

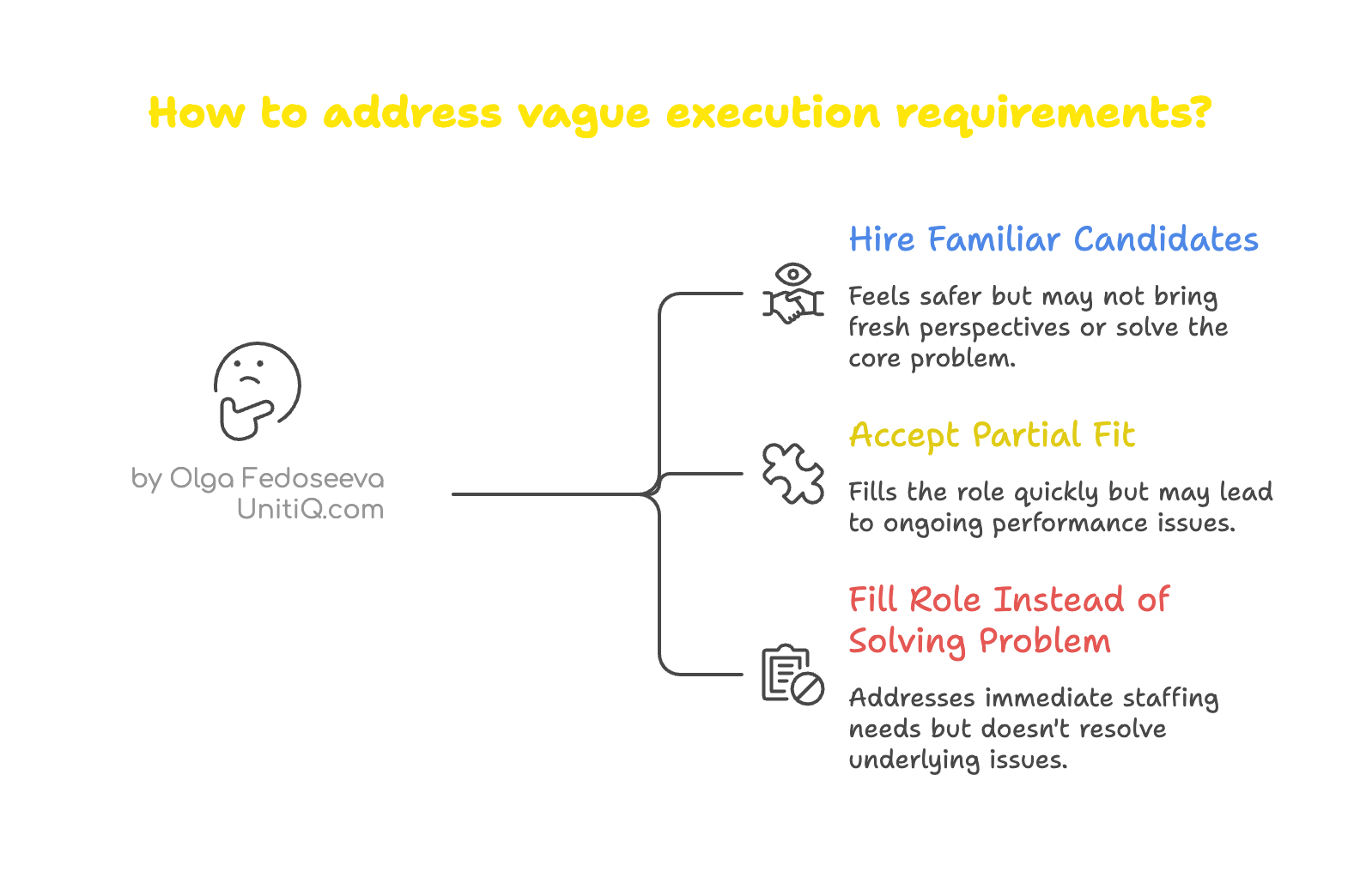

Why Teams Compromise When Execution Is Vague

Compromising isn’t a character flaw.

It’s a response to uncertainty.

When no one can clearly articulate:

- what “good execution” looks like, or

- how success will be measured,

teams default to risk minimization:

- hiring someone familiar

- accepting partial fit

- filling the role instead of solving the problem

This pattern is common when hiring is treated as episodic instead of continuous, rather than supported by a consistent, execution-focused hiring model.

This feels safer in the moment — and quietly increases long-term cost.

Why “Almost Right” Is More Expensive Than a Wrong Hire

Wrong hires fail visibly.

“Almost right” decisions fail silently.

They extend interview cycles, keep founders involved longer, delay momentum without triggering alarms, and normalize compromise as caution.

Over time, teams learn the wrong lesson:

that clarity is dangerous, speed is reckless, and indecision is responsible.

The real cost isn’t the candidate you didn’t hire.

It’s the execution capacity you never unlocked.

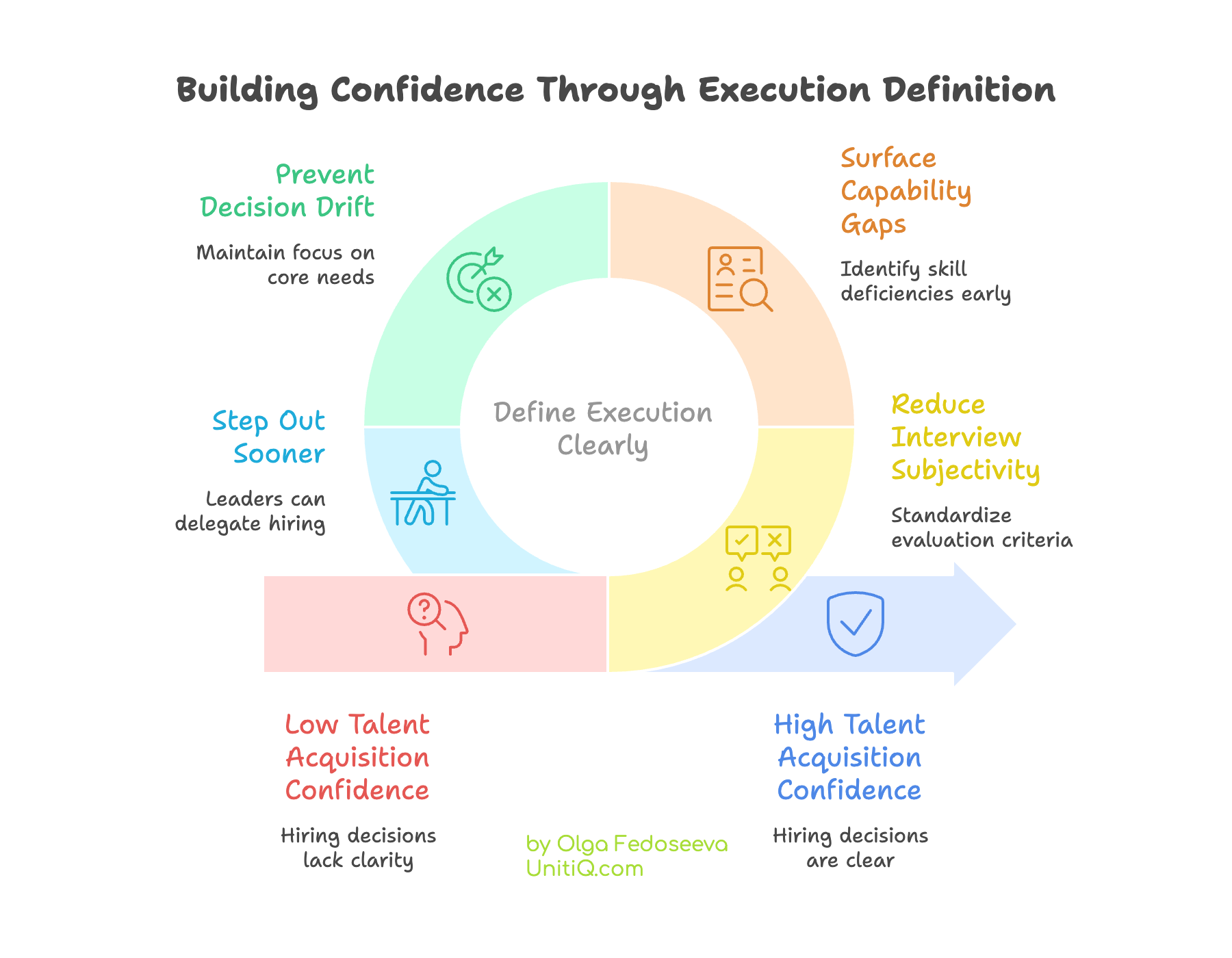

Execution Definition Is the Foundation of Talent Acquisition Confidence

High-performing teams don’t hire better people by default.

They define execution better.

Clear execution definitions:

- reduce interview subjectivity

- surface real capability gaps early

- prevent decision drift

- allow leaders to step out of hiring mode sooner

Without it, no amount of interviews, scorecards, or assessments will restore confidence.

Over time, unresolved “almost right” decisions don’t just slow hiring — they create hidden costs that quietly erode execution and leadership focus.

This article is part of a series on reducing uncertainty in talent acquisition:

– Uncertainty Is the Real Enemy of Talent Acquisition

– Talent Acquisition Breaks When Everyone Has a Signal — but No One Owns the Decision

– The Hidden Cost of Hiring Uncertainty

– Uncertainty Is the Real Enemy of Talent Acquisition

– Talent Acquisition Breaks When Everyone Has a Signal — but No One Owns the Decision

– The Hidden Cost of Hiring Uncertainty

“Almost Right” Is the Last Symptom Before Hiring Stops Working

By the time “almost right” starts repeating, execution expectations are already vague, ownership is already diffused, and founders are already pulled back into decisions.

This is why fixing interviews doesn’t help.

And why adding more candidates doesn’t change outcomes.

Hiring only starts working again when execution is defined before sourcing, decisions are owned rather than shared, and success is explicit enough to commit to.

Until then, “almost right” isn’t caution.

It’s drift.

TL;DR — Key Takeaways

- “Almost right” candidates are a signal of undefined execution, not weak talent

- CVs and titles cannot resolve execution ambiguity

- Undefined execution creates conflicting interview signals and slow decisions

- Clear execution definitions align interviews, ownership, and confidence

- Hiring confidence starts before sourcing — not during interviews

If you want to sanity-check what’s breaking in your hiring system, we can walk through it together.

👉 Book a conversation

👉 Book a conversation

About the author

Olga Fedoseeva is the Founder of UnitiQ, a talent acquisition and People Projects partner for Series A–C tech startups across EU, UKI, and MENA.

She works with founders in Fintech, AI, Crypto, and Robotics who are stuck in hiring or execution mode — helping them restore momentum by redesigning hiring around execution, ownership, and real outcomes.