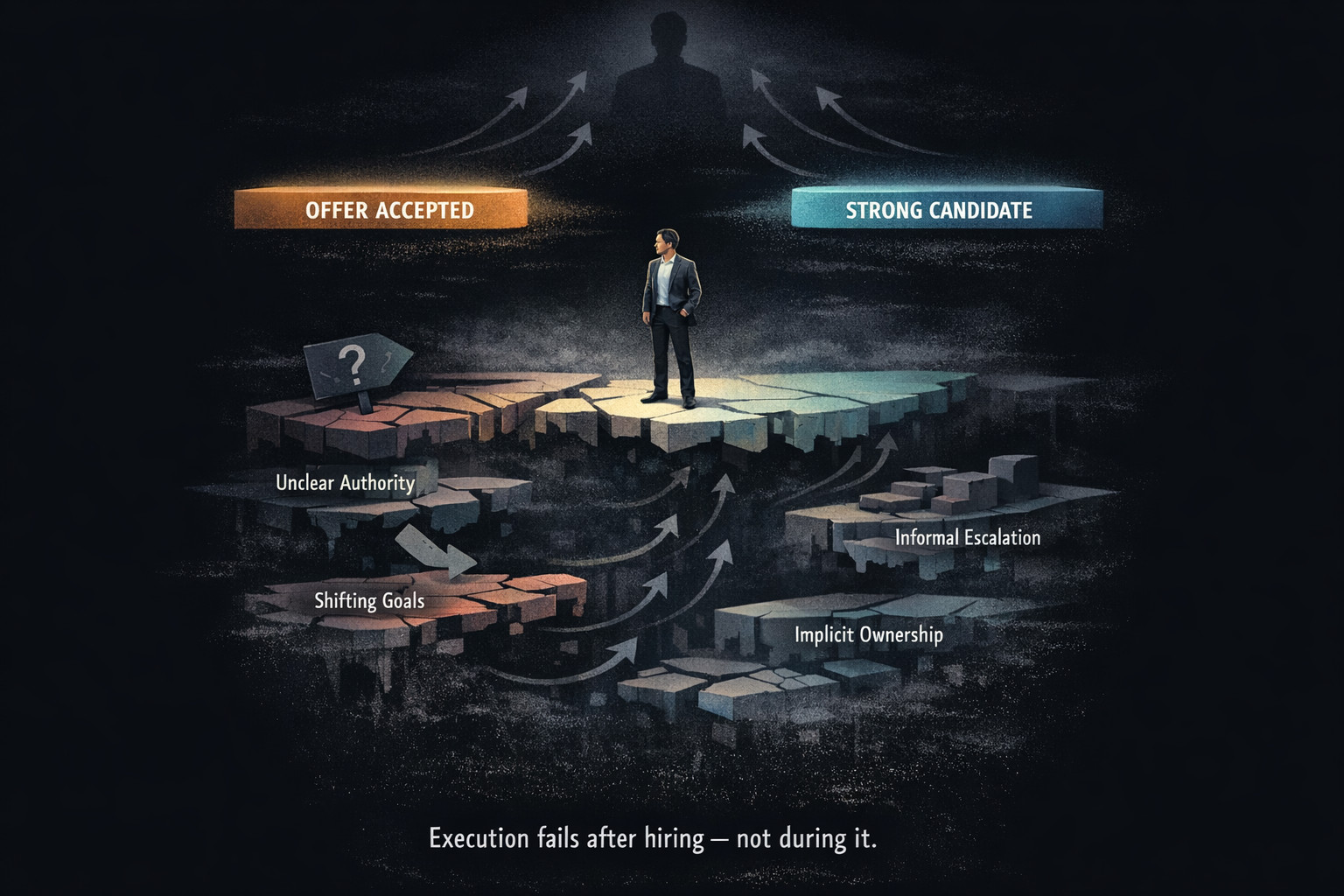

Most hiring failures don’t look like hiring failures.

The candidate was strong.

The interviews went well.

The offer was accepted quickly.

Everyone felt confident on day one.

And yet, within the first 60–90 days, something starts to slip.

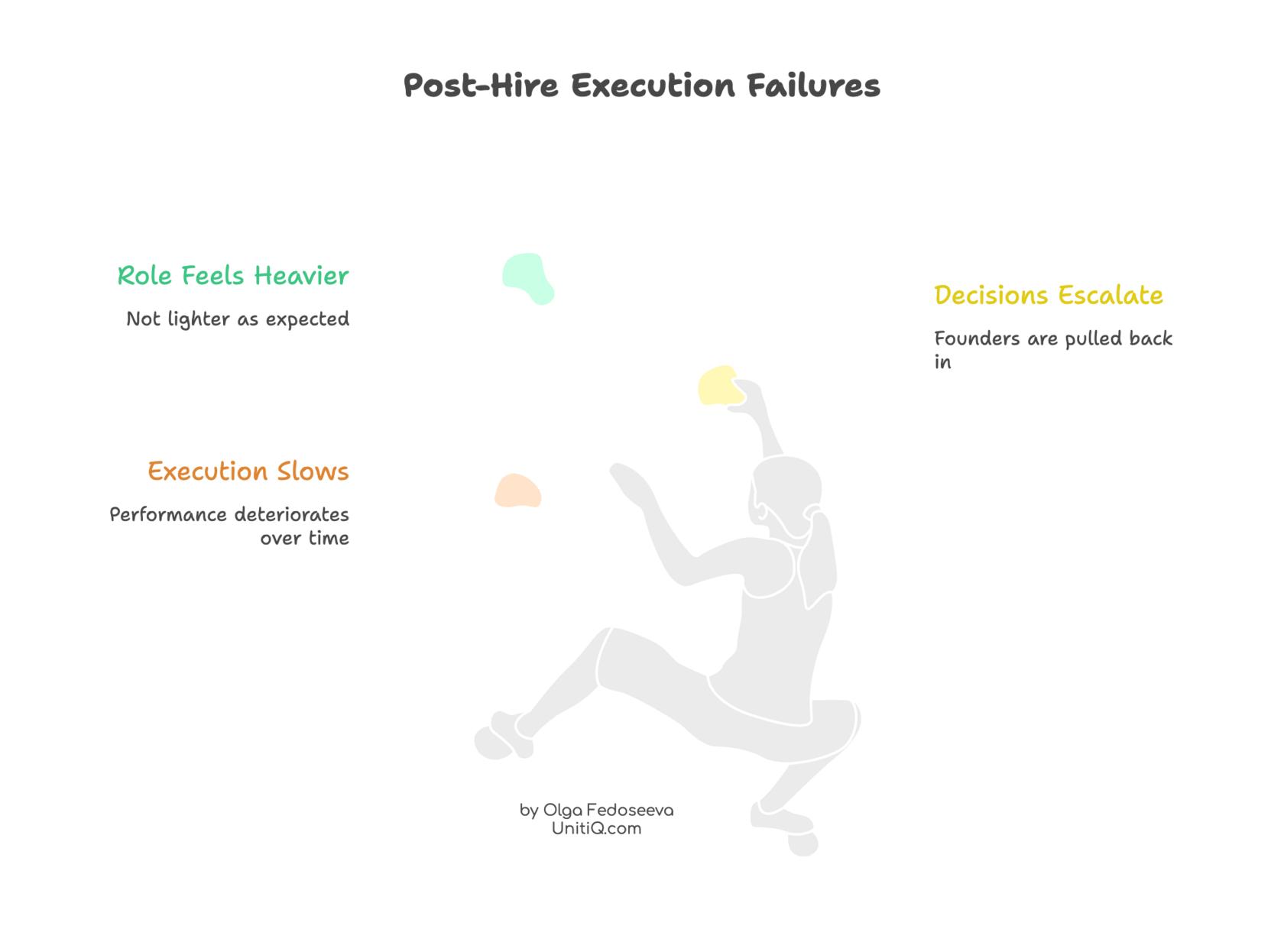

Execution slows.

Decisions escalate.

Founders get pulled back in.

The role feels heavier than expected — not lighter.

This isn’t a bad hire.

It’s a post-hire execution failure.

This pattern is rarely visible during interviews — it emerges after onboarding, when execution design can’t absorb new ownership. (Read: Execution Fails After Hiring — Not During It)

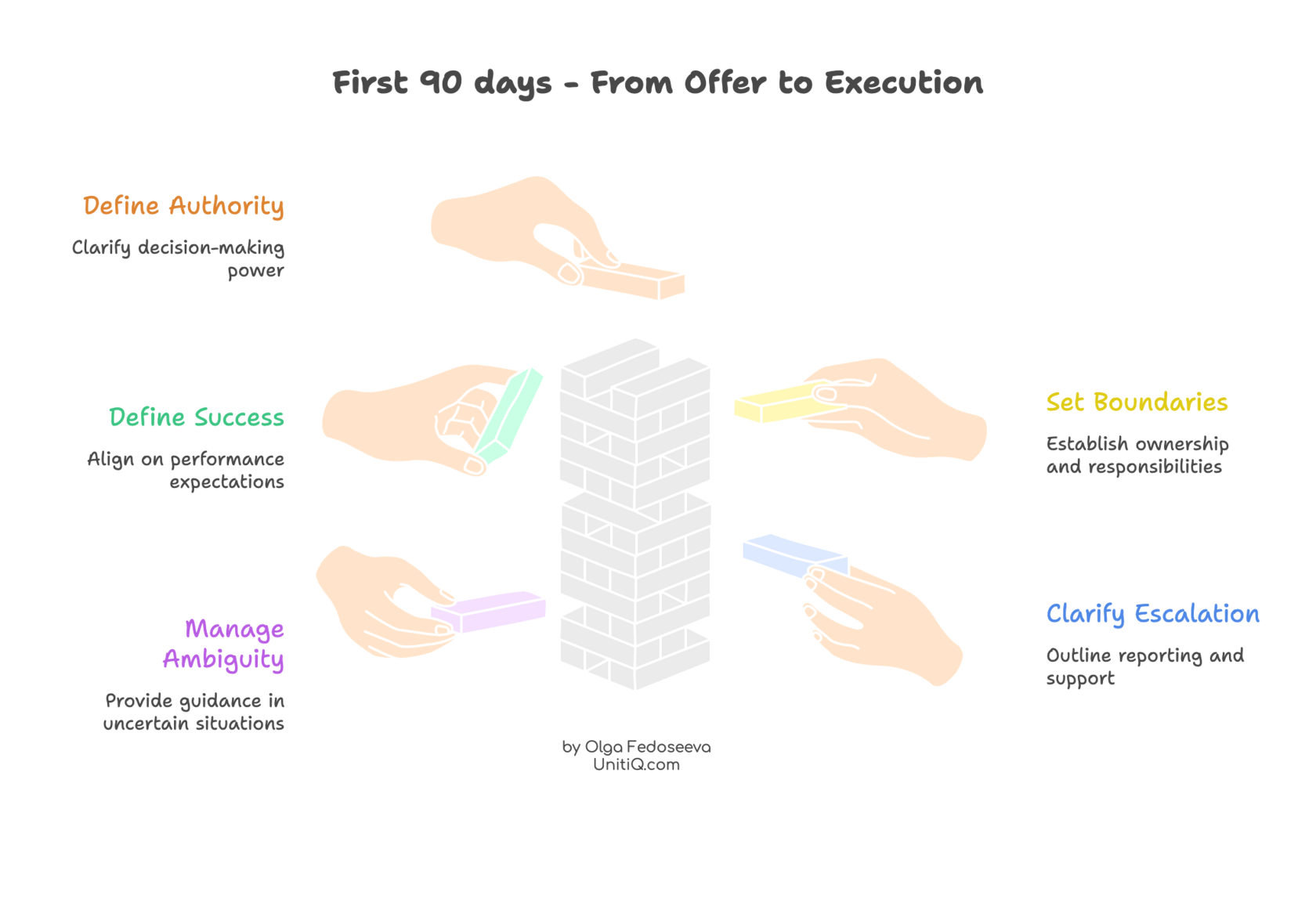

The First 90 Days Are Where Hiring Actually Succeeds or Fails

Startups often treat hiring success as a moment:

offer accepted

start date confirmed

role “closed”

But hiring doesn’t end when someone joins.

That’s when execution risk begins.

In the first 90 days, a new hire tests:

- decision authority

- ownership boundaries

- success definitions

- escalation paths

- tolerance for ambiguity

If those are unclear, even excellent hires stall.

Not because they lack skill.

Because the system gives them nowhere to stand.

The Hidden Pattern Behind Early “Underperformance”

When founders describe early post-hire problems, the language sounds familiar:

- “They’re capable, but hesitant.”

- “They keep checking before deciding.”

- “They’re busy, but nothing really moves.”

- “We expected more ownership by now.”

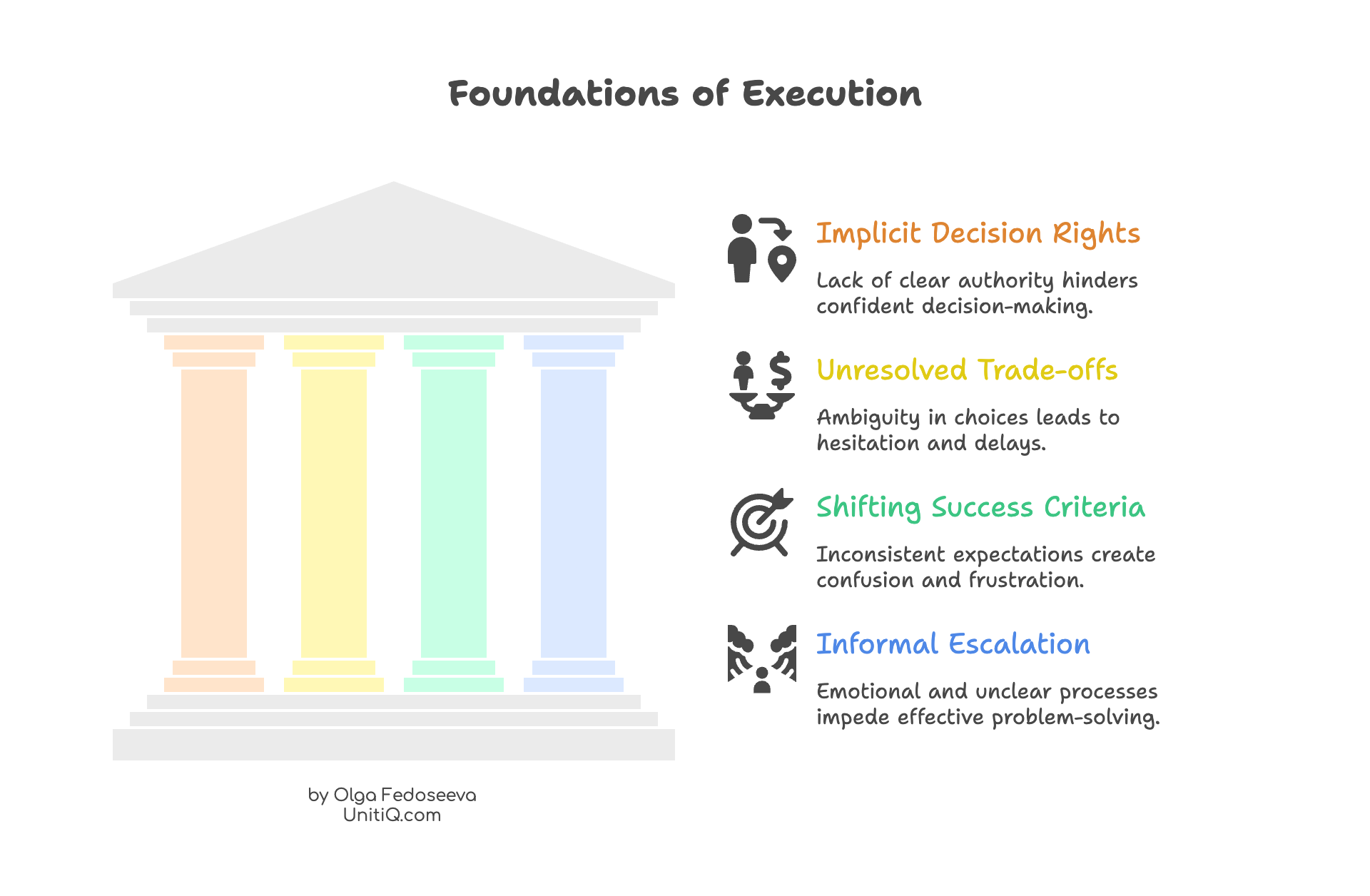

These are not performance issues.

They are authority issues.

When decision rights remain implicit, escalation replaces ownership — and performance appears weaker than it actually is. (Read: Fixing Decision Authority in Scaling Startups)

A hire cannot execute confidently when:

- decision rights are implicit

- trade-offs are unresolved

- success criteria shift after onboarding

- escalation is informal and emotional

So the hire slows down.

And execution quietly leaks upward.

Many teams respond to this slowdown by accelerating hiring — assuming it’s a capacity issue rather than an authority issue. That rarely solves the real bottleneck. (Read: Why Hiring Faster Won’t Fix Your Execution)

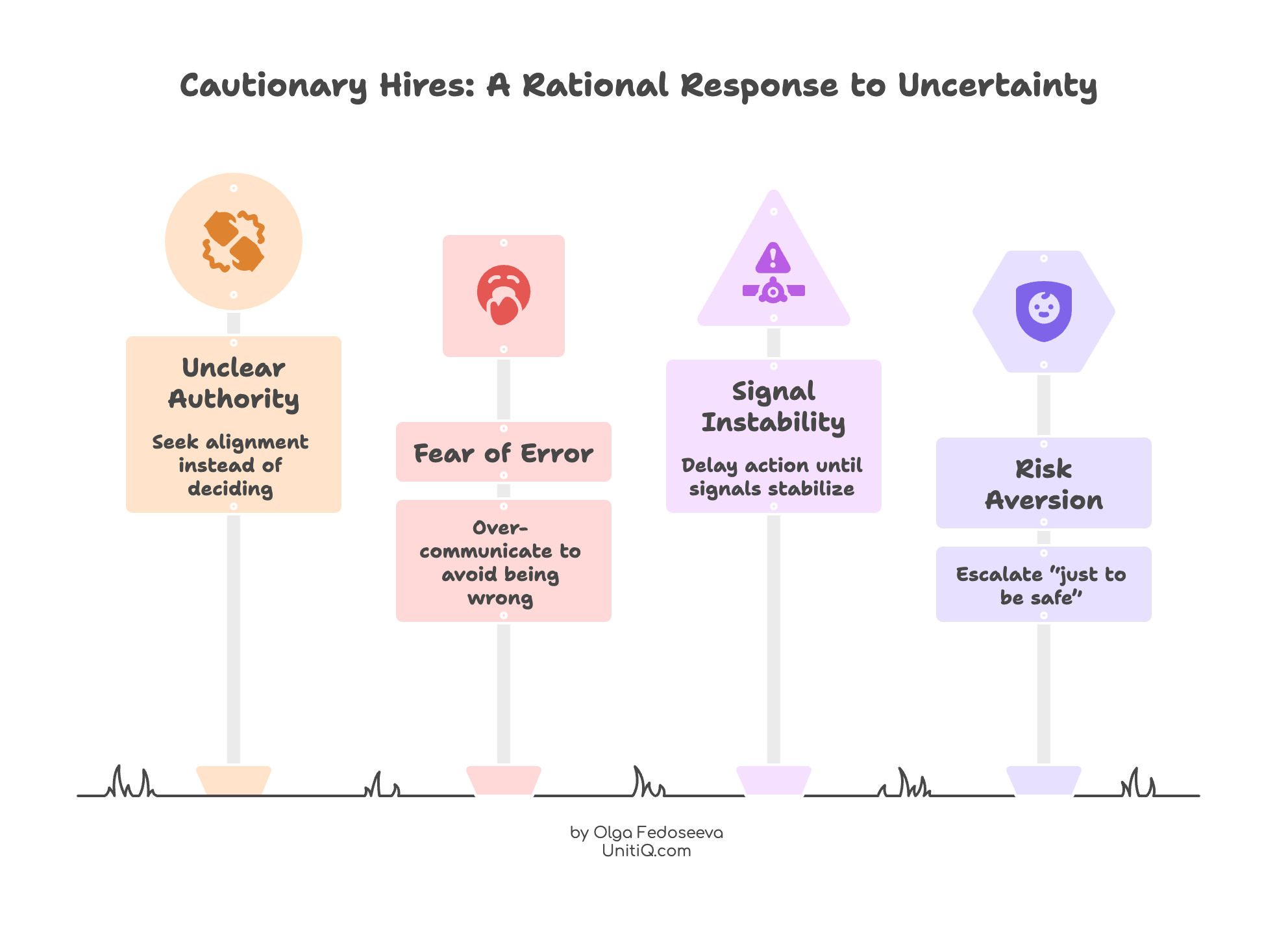

Why Strong Hires Default to Caution

Experienced operators don’t fail loudly.

They adapt.

When authority is unclear, they:

- seek alignment instead of deciding

- over-communicate to avoid being wrong

- delay action until signals stabilise

- escalate “just to be safe”

From the outside, this looks like:

lack of ownership

low initiative

over-collaboration

In reality, it’s a rational response to uncertainty.

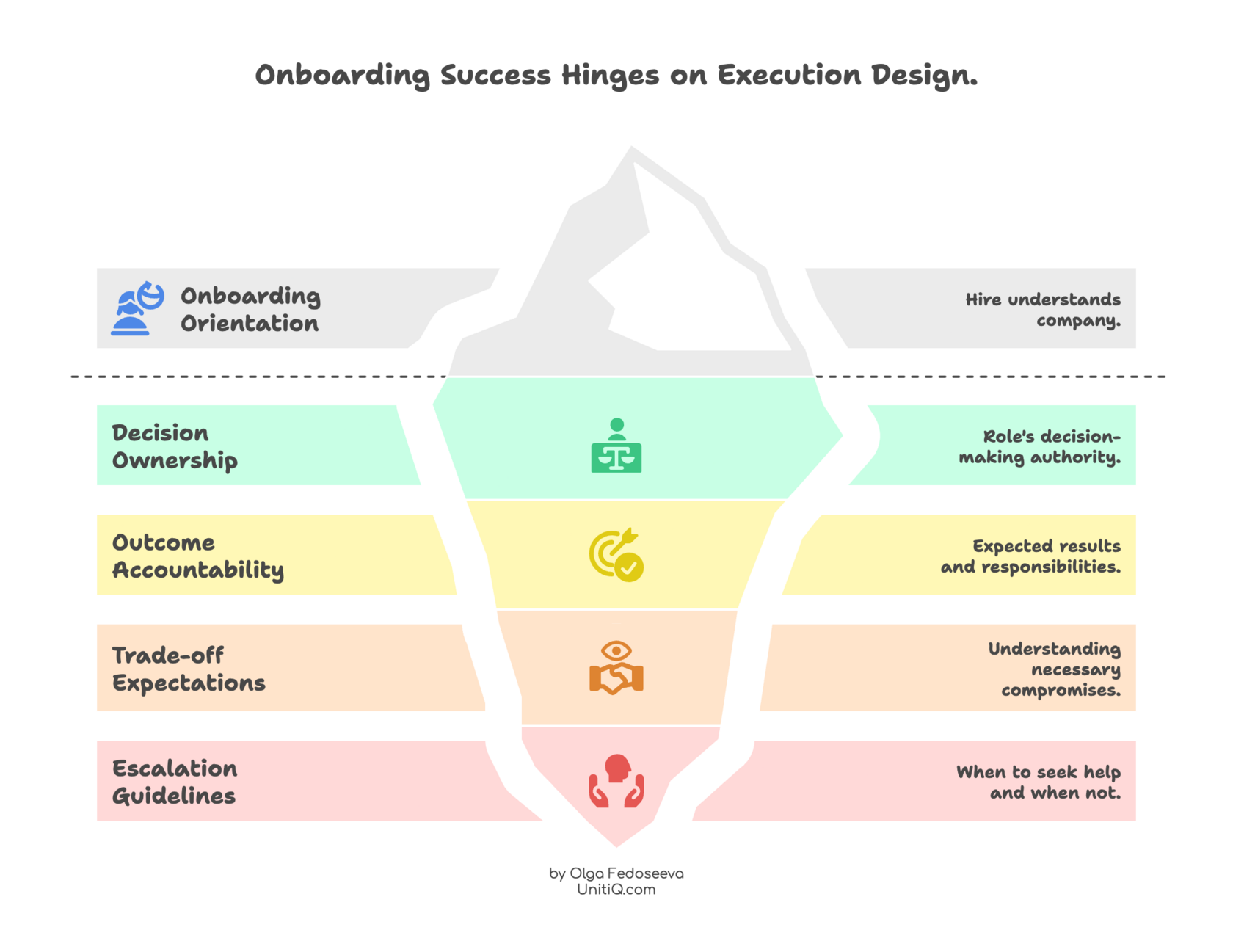

Onboarding Doesn’t Fail — Execution Design Does

Most onboarding focuses on:

- tools

- processes

- people

- culture decks

What’s often missing:

- What decisions this role owns

- What outcomes they’re accountable for

- What trade-offs they’re expected to make

- When escalation is required — and when it isn’t

Without that clarity, onboarding becomes orientation.

Not enablement.

The hire understands the company — but not their authority within it.

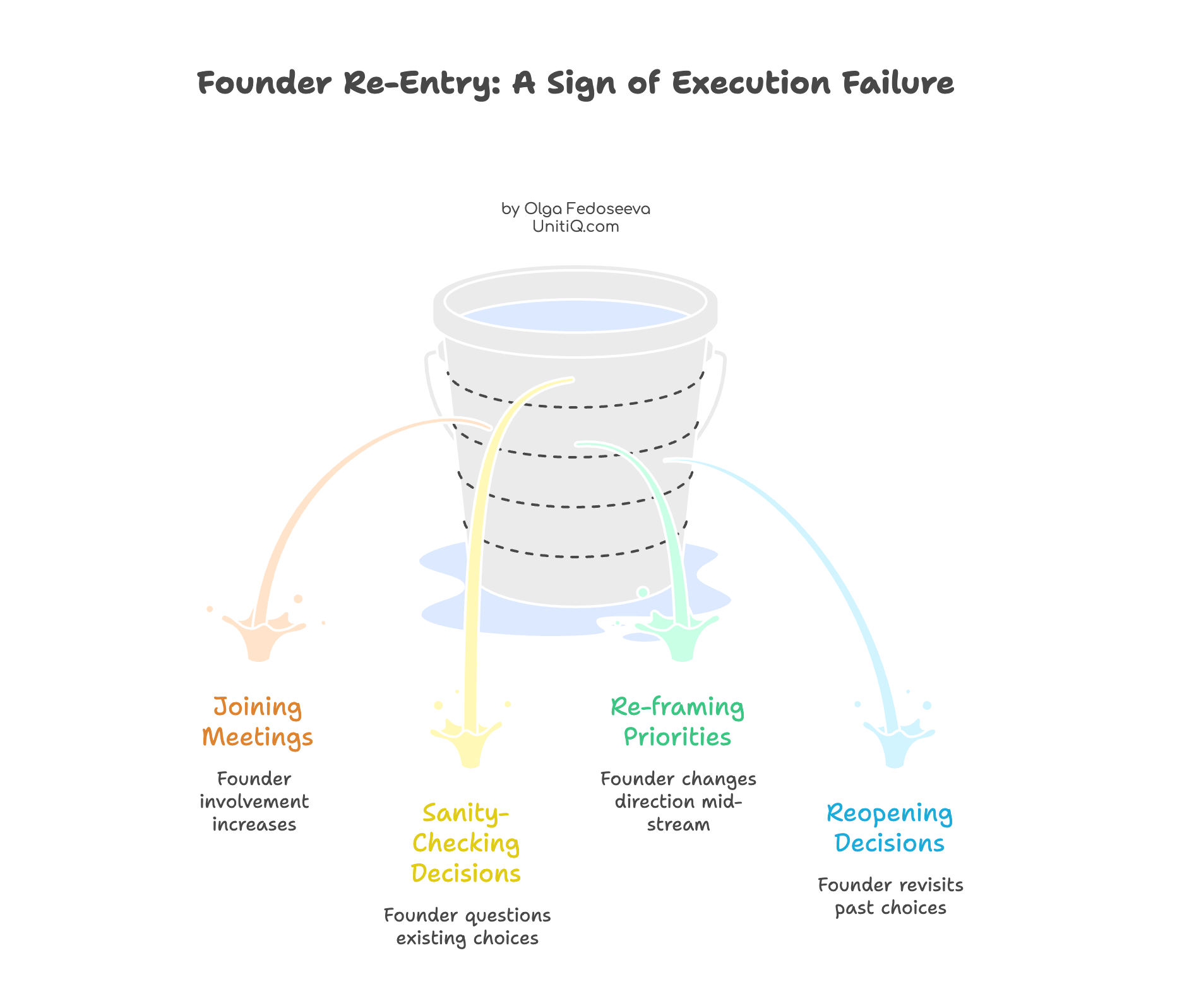

The Founder Re-Entry Signal

One of the clearest signs of post-hire execution failure is founder behaviour.

Watch for:

- founders “joining a few meetings”

- founders “sanity-checking decisions”

- founders re-framing priorities mid-stream

- founders reopening decisions already made

This isn’t micromanagement.

It’s a system absorbing unresolved risk.

When execution isn’t contained inside the role,

it flows back to the founder.

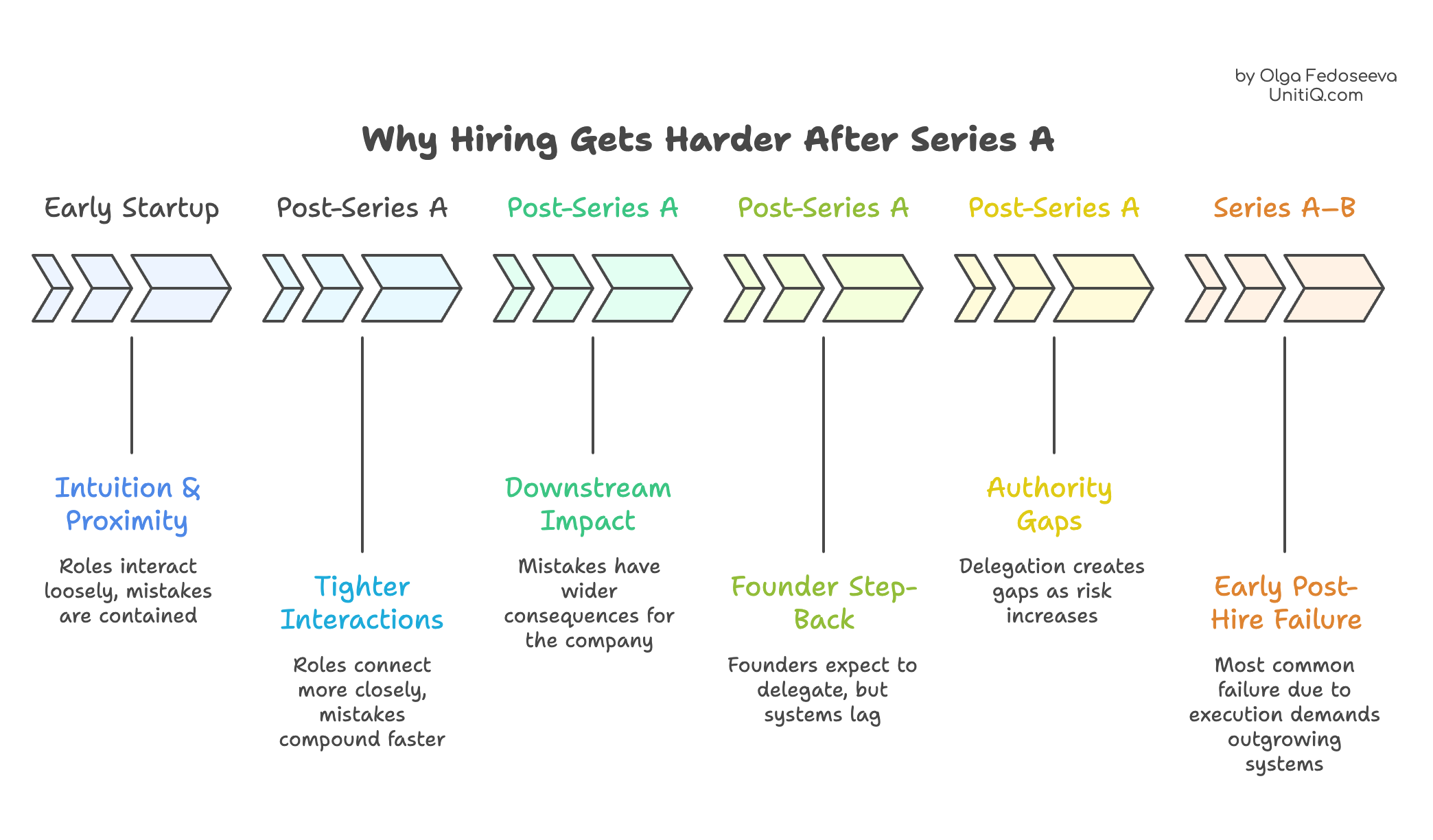

Why This Happens More After Series A

Early startups survive on intuition and proximity.

Growth-stage companies cannot.

After Series A:

- roles interact more tightly

- mistakes compound faster

- downstream impact increases

- founders expect to step back

But hiring systems often remain designed for early stage.

When hiring isn’t treated as infrastructure — with explicit role architecture and escalation logic — context resets with every new role. (Read: Building Hiring Infrastructure for Scale)

So authority gaps widen just as risk increases.

That’s why early post-hire failure is most common in Series A–B companies —

not because hiring got worse,

but because execution demands outgrew the system.

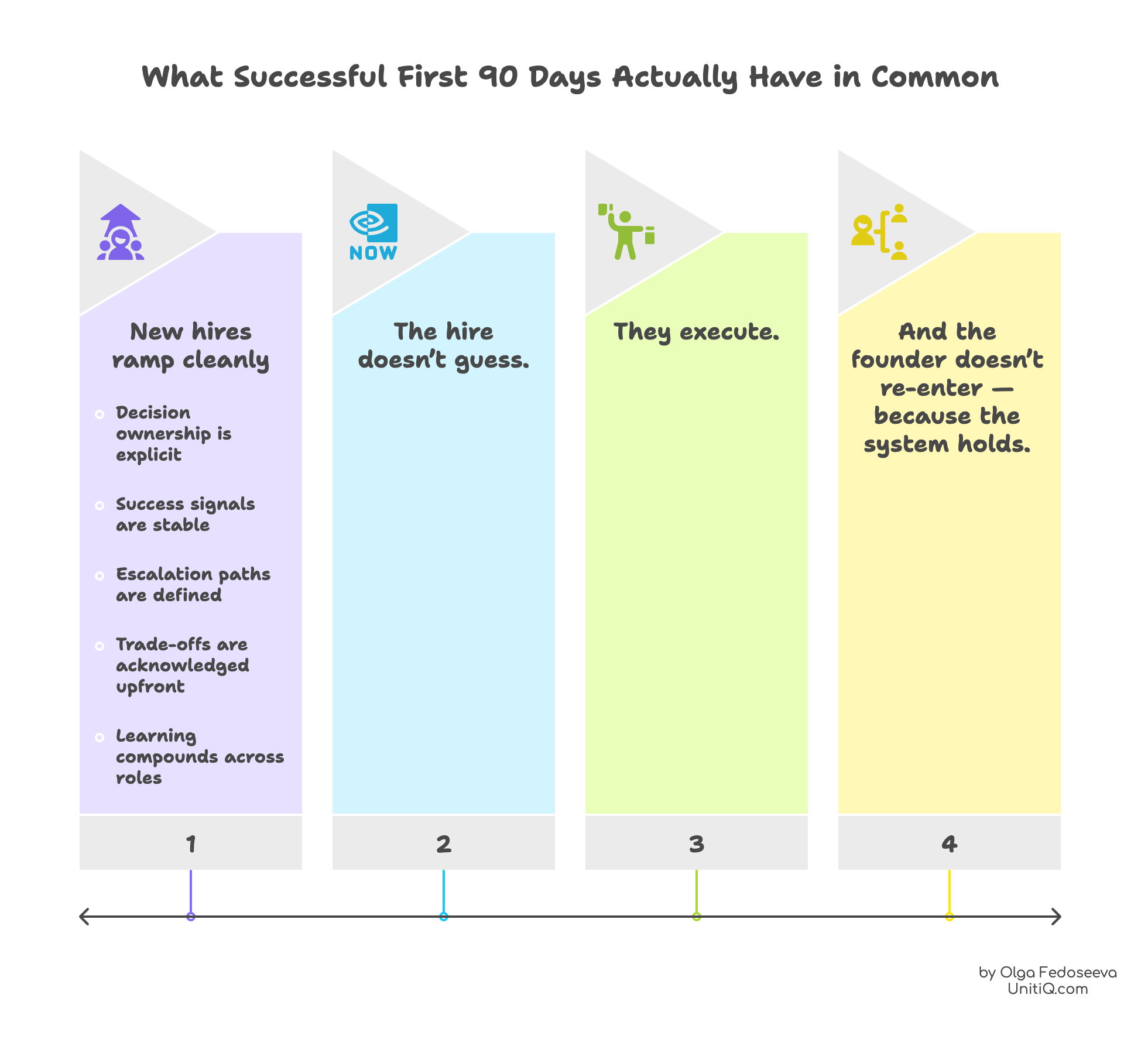

What Successful First 90 Days Actually Have in Common

In teams where new hires ramp cleanly:

- decision ownership is explicit

- success signals are stable

- escalation paths are defined

- trade-offs are acknowledged upfront

- learning compounds across roles

When hiring is treated as a series of isolated recruitment events instead of a compounding system, each new hire restarts the learning curve. (Read: Why Event-Based Hiring Keeps Resetting Your Startup)

The hire doesn’t guess.

They execute.

And the founder doesn’t re-enter —

because the system holds.

When the system doesn’t hold, founders quietly absorb unresolved risk — and burnout often begins long before hiring goals are met. (Read: Why Founders Burn Out on Hiring Before It’s “Done”)

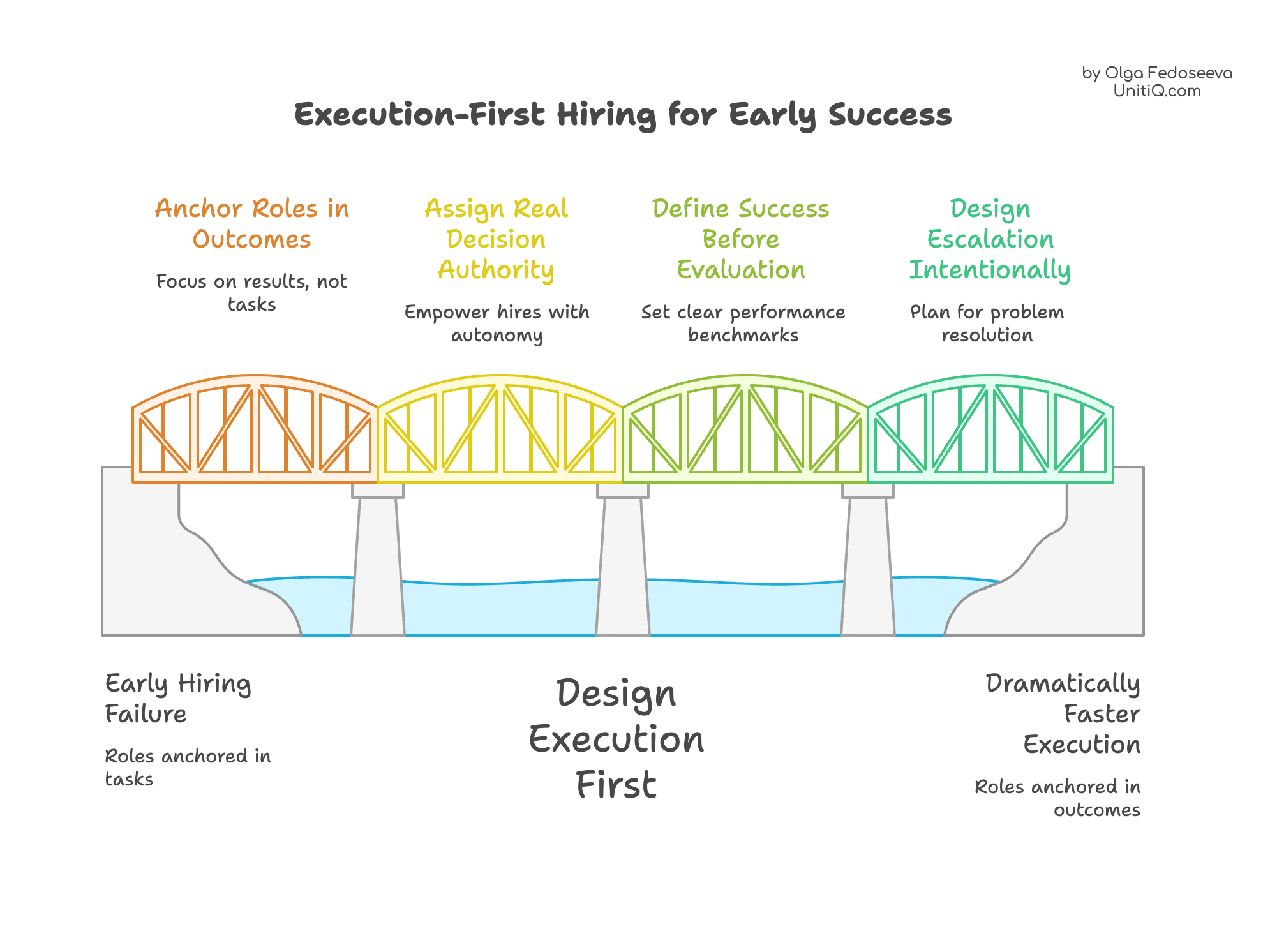

Fixing the First 90 Days Is a Hiring Problem — Just Not the One You Think

You don’t fix early failure by:

- changing interview questions

- hiring “more senior”

- adding onboarding checklists

- extending probation periods

You fix it by designing execution before the hire starts.

That means:

- anchoring roles in outcomes, not tasks

- assigning real decision authority

- defining success before evaluation begins

- designing escalation intentionally — not emotionally

This is why execution-first hiring feels slower upfront —

and dramatically faster after.

TL;DR

- Most hiring failures happen after the offer, not before

- Early underperformance is usually an authority gap

- Strong hires default to caution when signals are unclear

- Founder re-entry is a system alarm, not a leadership flaw

- The first 90 days succeed when execution is designed, not improvised

If a “good hire” isn’t delivering momentum yet,

don’t replace them too quickly.

First ask:

what execution system did they actually step into?

---

If you want to sanity-check which model fits your current stage — and where execution is actually breaking — we can walk through it together.

About the author

Olga Fedoseeva is the Founder of UnitiQ, a global HR executive, and a talent acquisition and people strategy leader with 20+ years of experience across EMEA, the US, and APAC. She has personally hired 1,500+ employees, led people strategy for organisations scaling from 30 to 700+ employees, and writes about hiring systems, execution risk, and people infrastructure in growth-stage startups.

Read full author profile

LinkedIn

Read full author profile